Saturday, December 31, 2005

The Mystery of the Watermelons

It seems that St. Benard Parish, which was almost completed destroyed by the Katrina storm surge up the MRGO, is bursting out in watermelons.

"I've never seen anything like this before," Dr. Ron Strahan of the LSU Ag Center as told WAFB-TV in Baton Rouge after he surveyed the watermelon infestation.

The fruit, which is normally planted in April, has been sprouting up all over St. Bernard Parish ever since Katrina, due in part to unusually high temperatures.

While the good doctor may be mystified, some research turns up gardeners who aren't. The watermelon seeds were likely present in untreated or partially treated sewage. In St. Bernard, just east of New Orleans, the sewage likely spilled during the complete innundation of the parish.

The use of treated sewage--henceforth to be called "biosolids"-- is being promoted as a fertilizer, to be used like animal manure. Some early adopters on GardenWeb.com had some interesting results.

While funny, it is also interesting, if not disturbing. The distribution of watermelons may correspond with the distribution of spilled sewage.

Think New Orleans

"I've never seen anything like this before," Dr. Ron Strahan of the LSU Ag Center as told WAFB-TV in Baton Rouge after he surveyed the watermelon infestation.

The fruit, which is normally planted in April, has been sprouting up all over St. Bernard Parish ever since Katrina, due in part to unusually high temperatures.

While the good doctor may be mystified, some research turns up gardeners who aren't. The watermelon seeds were likely present in untreated or partially treated sewage. In St. Bernard, just east of New Orleans, the sewage likely spilled during the complete innundation of the parish.

The use of treated sewage--henceforth to be called "biosolids"-- is being promoted as a fertilizer, to be used like animal manure. Some early adopters on GardenWeb.com had some interesting results.

"I put some sewage sludge on an ornamental garden one year. I got a laugh, wall to wall tomato plants with a few cantalope and watermelon thrown in. I just left them for the frost to kill, there was no way I could pull them all," one reported.

While funny, it is also interesting, if not disturbing. The distribution of watermelons may correspond with the distribution of spilled sewage.

Think New Orleans

Thursday, December 29, 2005

Sitting here in limbo

Sitting here in limbo, but I know it won't be long

Sitting here in limbo, like a bird without a song

Well they're putting up resistance

But I know my faith will lead me on

-- Jimmy Cliff

I wore out my vinyl copy of the soundtrack to the movie Harder They Come

My theme for today, however, isn't the anti-heroes of the 1970s. We are long past the days when their was anything romantic about the anti-heroes of this movie. The drug gangsters are gone from New Orleans (for now), and good riddance.

This reggae spiritual is the sound track in my head as I sit here 1,200 miles and twenty years removed from my city and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, replacing the unrelenting loop of Adagio for Strings that haunted me through September and into October, and was then replaced by the piece Requiem , a haunting piece of music originally composed by Eliza Gilkyson for for the victims of the Christmas tsunami.

Mother Mary full of grace, awaken.

All our homes and all our loved ones taken.

Taken by the sea.

Hear our mournful plea.

Mother Mary find us where we've fallen

Out of grace.

Lead us to a higher place.

If you can listen to this carefully without crying, check your pulse or the mark on the front of your house, cap, cause you're dead.

But now I read day after day about the seeming normality of life for those lucky few on what a WWOZ DJ referred to as "the sliver by the river", a town smaller than Fargo, N.D. where I sit writing this. And then I get an email from someone who's taken a series of photos of the rest of the city after dark, in the dark. I read about the latest post-K suicides here and here and ...

Congress passed a Katrina relief bill, but most of the $29 Billion went to FEMA or other branches of the federal government, which means that real people mostly will never see it. No one will step up to help pay $350 million to rebuild Entergy's infrastructure in the city, including the stockholders of the parent company who have been perfectly happy to harvest the profits in the past.

Congress adjourned without action on the Baker Bill, which would provide direct assistance to those who lost their homes. Without this bill, hundreds of thousands of Americans will have to pay out the mortgages on their ruined, worthless properties. Baker has promised to bring it back, but the people's House is adjourned until Jan. 31, meaning no action can begin before February.

The city's leaders can't seem to make a decision on how reconstruction should proceed, while the usual political factions bicker over where FEMA trailers should be place. The rest of the country seems to think we're too corrupt to take care of ourselves, so they're perfectly OK that we've suspended elections for the time being.

So, we're all left (well, I am at least) with Jimmy Cliff's voice echoing around in my head, in a mournful sort of way. Ah, but then, we have to remember, Sitting in Limbo was just one of the fabulous songs in that movie. And it was not the title song. This was.

Persecution you must bear

Win or lose you've got to get your share

Got your mind set on a dream

You can get it, though harder them seem now

You can get it if you really want

But you must try, try and try

Try and try, you'll succeed at last

You can get it if you really want - I know it

You can get it if you really want - though I show it

You can get it if you really want

- so don't give up now

Wednesday, December 28, 2005

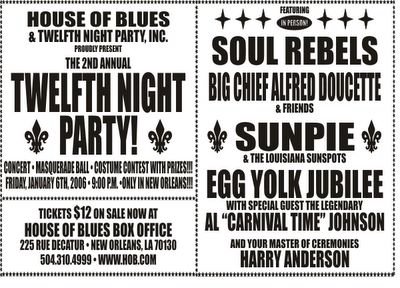

Benefit for Big Chief Alfred Doucette

Proceeds from this Twelth Night party will help defray the cost of Big Chief Alfrd Doucette's big chief costume. With all of the things people have lost and can't replace after Katrina, I have to say this: if we can't replace the soul of New Orleans, the rest of it isn't worth having. The Indian tradition is so much a part of the city's soul, it must be saved.

Saturday, December 24, 2005

All I want for Xmas is New Orleans

There is an old convention in journalism that we bloggers, as the New Journalists of the 21st Century, will feel bound to observe: the Christmas piece. As a former reporter, I can't seem to resist the temptation. But it's more than dragging out the fir and lights; it's a deeply ingrained desire to say or do something good at this time of year.

All I want for Christmas is New Orleans.

How easily this conventional, almost trite sentiment comes to mind. But it is true. Even for a 20-year ex-pat, there is nothing I want more. Outside of my wife and kids, there is nothing dearer to my heart than the home I left behind New Year's Eve 1986. Like most first-generation emigrants (and I have always considered myself an immigrant to the United States from the Republic of New Orleans), I have never, could never break the ties of place to my only real home.

And since I said to my wife back in late September "I want to move back to New Orleans" and she, instead of spitting wine all over herself in convulsive laughter, said yes, its become even more important to me personally, and not just because I was what Dr. John called traumaticalized in a recent Chris Rose column in the T-P.

At an age when my kids are more than halfway grown, and I sit and contemplate what to do with the rest of my life, I can't think of anything I want to do more than be a part of the future of New Orleans. Anything else will, for me, be an excuse for a life, the poet's quiet desperation of hanging on until it's over.

That's not a life.

I have no illusions about what was lost. Hell, the city I left in my rear view mirror nineteen years ago was not the city I grew up in. So much had been lost already to the relentless floods of time and American commerce; so much more was swept away between that New Year's Eve when I left and the flood. But the failure of local stores, as dear as they were to us all, was not a New Orleans problem. It was an American problem, happening everywhere. Losing D.H. Holmes or K&B were a disappointment. But that was not the same as losing the neighborhood bars and restaurants and stores, all threatened in the aftermath of Katrina and the flood.

Much that remains the same would not be missed if it could somehow be carried away with the ruined appliances and the moldy drywall: the crime that blossomed in New Orleans just like in every other heavily poor and black urban area, the political division and bickering that separated New Orleanians into warring camps, the corruption of the School and Levee Boards.

And there are the embarrassing headlines about the N.O.P.D. or Bourbon Street bartenders, the remarks sitting in my inbox today from various lists about the people Gretna Mayor Ronnie Harris called "the criminal element" in his 60 Minutes interview. You know who I mean. Many of the people I hear complaining the loudest about Mama D must have lost all their mirrors to Katrina, because they could mostly use a long, hard look in one.

I won't accept just resettling, merely rebuilding New Orleans. Somehow, it must be better, fairer, less poor and less divided, and still every bit as much the city of memory and dreams. Not many cities are presented with the opportunity of starting over from scratch on such a vast scale, being given a second chance to do things right.

The New Orleans of my Christmas wish is not just the town I grew up in, or the town I constantly pine for on some level--the city of food and friends, of music and Mardi Gras--it is for a city where people make a decent living and can afford to own and fix up their homes, where the schools and police and the levees work at least as well as most other places, where the unifying spirit of resettlement and recovery breaks down the fear that divides Audubon Place from Almonaster, separates Lakeview from Lafitte.

It should be a place that is rebuilt for the benefit of it's people, and not at the whims of the market-place that's already left so many of them behind, the invisible hand that turned the last jazz club on Bourbon Street into a karaoke bar, the idol Mammon that would demolish everything to rule over a thousand suburban boulevards lined with box stores, that would be perfectly appeased to make New Orleans into an historic shell for upscale boutiques.

Only if a critical mass of people come home can what is good be saved, and what is not be averted. I understand why some people who lived in crime-ridden neighborhoods would stay in their newly adopted homes, why others who sacrificed the high salaries of elsewhere to live in New Orleans might find it hard to return home to sub-market wages and inflated rents.

Good luck to you all. But you may find, five or ten or twenty years from now, that you have never really been happy living in your new home. The city’s pull will begin to work at you. You will want to go home.

That’s my Christmas Wish, not just to come home, but to be part of one of the great stories, the one about miraculous births and resurrections. There are so many pieces that must fall into place, so many immense hurdles to overcome--multiplied by the hundreds of thousands, once for each of us--it seems only a miracle will do.

But I believe in Christmas miracles. A decade ago, my three-year old daughter fell in love with a character called Rugby Tiger, from an obscure Muppet’s movie call the Christmas Toy. Having Rugby Tiger was her only Christmas wish, the only secret she had for Santa.

Finding Rugby Tiger proved to be impossible. The Christmas Toy is a wonderful show, but not a spectacular of the sort that generates tie-in marketing. The stores at Christmas are full of great piles of stuffed animals, but none came close to looking like Rugby. We scoured the smallish town we lived in at the time, and all the stores of Fargo, N.D. as well. I dredged through catalogs online stores back in the early days of e-commerce, and called every major toy store I could think of. It became increasingly clear there would be no miracle, that the first Christmas my first child really understood would be a failure, a disappointment that would haunt her the rest of her life.

There’s a happy holiday thought.

Then one day, perhaps a week before Christmas, I went into a little mom-and-pop drug store in little Detroit Lakes, MN, and walked past the big pile of stuffed animals I had twice before torn apart. As I came back from the pharmacist with my little bag, I decided to have one last desperate dig. And that’s when I found him.

His tag didn’t say Rugby Tiger, but he was a perfect replica, the very image of the television tiger. Christmas was saved.

I’ve told this story to my children, when they finally asked me about Santa Claus. Yes, I can tell them with a straight face, I do believe in Santa Claus, because once when I truly needed a mieraculous Christmas present for someone I loved, it happened.

Perhaps I’ve used up my quotient of miracles. But I know that belief is more than just a bit of sustaining psychology. I am a poor excuse for a Christian, probably not one at all at this point in my life. But I know there is a power within us and without us that, sustained by belief, can work miracles in this world.

Most miracles are small and personal things: two people meeting and falling in love, a child’s face on Christmas morning when they find a dream come true, the birth on a winter’s night of a child entirely ordinary and no less miraculous. My Christmas wishes for myself and for my city may seem as improbable as the sentiments of a beauty contestant, but they’re not. My wish is for the thousand tiny and entirely human miracles I know are possible.

My wish is that at this holiday, somewhere in America, the separated parts of a family come together in exile--a little more complete—and begin their plans to go home; that somewhere in a line at a government office, two people discover that the other is not a greedy white boss or a scary black criminal, but someone with whom they share memories and hopes; that someone will come home today and, when the tears have finally stopped, they will begin again their life in New Orleans.

I'll see you there.

All I want for Christmas is New Orleans.

How easily this conventional, almost trite sentiment comes to mind. But it is true. Even for a 20-year ex-pat, there is nothing I want more. Outside of my wife and kids, there is nothing dearer to my heart than the home I left behind New Year's Eve 1986. Like most first-generation emigrants (and I have always considered myself an immigrant to the United States from the Republic of New Orleans), I have never, could never break the ties of place to my only real home.

And since I said to my wife back in late September "I want to move back to New Orleans" and she, instead of spitting wine all over herself in convulsive laughter, said yes, its become even more important to me personally, and not just because I was what Dr. John called traumaticalized in a recent Chris Rose column in the T-P.

At an age when my kids are more than halfway grown, and I sit and contemplate what to do with the rest of my life, I can't think of anything I want to do more than be a part of the future of New Orleans. Anything else will, for me, be an excuse for a life, the poet's quiet desperation of hanging on until it's over.

That's not a life.

I have no illusions about what was lost. Hell, the city I left in my rear view mirror nineteen years ago was not the city I grew up in. So much had been lost already to the relentless floods of time and American commerce; so much more was swept away between that New Year's Eve when I left and the flood. But the failure of local stores, as dear as they were to us all, was not a New Orleans problem. It was an American problem, happening everywhere. Losing D.H. Holmes or K&B were a disappointment. But that was not the same as losing the neighborhood bars and restaurants and stores, all threatened in the aftermath of Katrina and the flood.

Much that remains the same would not be missed if it could somehow be carried away with the ruined appliances and the moldy drywall: the crime that blossomed in New Orleans just like in every other heavily poor and black urban area, the political division and bickering that separated New Orleanians into warring camps, the corruption of the School and Levee Boards.

And there are the embarrassing headlines about the N.O.P.D. or Bourbon Street bartenders, the remarks sitting in my inbox today from various lists about the people Gretna Mayor Ronnie Harris called "the criminal element" in his 60 Minutes interview. You know who I mean. Many of the people I hear complaining the loudest about Mama D must have lost all their mirrors to Katrina, because they could mostly use a long, hard look in one.

I won't accept just resettling, merely rebuilding New Orleans. Somehow, it must be better, fairer, less poor and less divided, and still every bit as much the city of memory and dreams. Not many cities are presented with the opportunity of starting over from scratch on such a vast scale, being given a second chance to do things right.

The New Orleans of my Christmas wish is not just the town I grew up in, or the town I constantly pine for on some level--the city of food and friends, of music and Mardi Gras--it is for a city where people make a decent living and can afford to own and fix up their homes, where the schools and police and the levees work at least as well as most other places, where the unifying spirit of resettlement and recovery breaks down the fear that divides Audubon Place from Almonaster, separates Lakeview from Lafitte.

It should be a place that is rebuilt for the benefit of it's people, and not at the whims of the market-place that's already left so many of them behind, the invisible hand that turned the last jazz club on Bourbon Street into a karaoke bar, the idol Mammon that would demolish everything to rule over a thousand suburban boulevards lined with box stores, that would be perfectly appeased to make New Orleans into an historic shell for upscale boutiques.

Only if a critical mass of people come home can what is good be saved, and what is not be averted. I understand why some people who lived in crime-ridden neighborhoods would stay in their newly adopted homes, why others who sacrificed the high salaries of elsewhere to live in New Orleans might find it hard to return home to sub-market wages and inflated rents.

Good luck to you all. But you may find, five or ten or twenty years from now, that you have never really been happy living in your new home. The city’s pull will begin to work at you. You will want to go home.

That’s my Christmas Wish, not just to come home, but to be part of one of the great stories, the one about miraculous births and resurrections. There are so many pieces that must fall into place, so many immense hurdles to overcome--multiplied by the hundreds of thousands, once for each of us--it seems only a miracle will do.

But I believe in Christmas miracles. A decade ago, my three-year old daughter fell in love with a character called Rugby Tiger, from an obscure Muppet’s movie call the Christmas Toy. Having Rugby Tiger was her only Christmas wish, the only secret she had for Santa.

Finding Rugby Tiger proved to be impossible. The Christmas Toy is a wonderful show, but not a spectacular of the sort that generates tie-in marketing. The stores at Christmas are full of great piles of stuffed animals, but none came close to looking like Rugby. We scoured the smallish town we lived in at the time, and all the stores of Fargo, N.D. as well. I dredged through catalogs online stores back in the early days of e-commerce, and called every major toy store I could think of. It became increasingly clear there would be no miracle, that the first Christmas my first child really understood would be a failure, a disappointment that would haunt her the rest of her life.

There’s a happy holiday thought.

Then one day, perhaps a week before Christmas, I went into a little mom-and-pop drug store in little Detroit Lakes, MN, and walked past the big pile of stuffed animals I had twice before torn apart. As I came back from the pharmacist with my little bag, I decided to have one last desperate dig. And that’s when I found him.

His tag didn’t say Rugby Tiger, but he was a perfect replica, the very image of the television tiger. Christmas was saved.

I’ve told this story to my children, when they finally asked me about Santa Claus. Yes, I can tell them with a straight face, I do believe in Santa Claus, because once when I truly needed a mieraculous Christmas present for someone I loved, it happened.

Perhaps I’ve used up my quotient of miracles. But I know that belief is more than just a bit of sustaining psychology. I am a poor excuse for a Christian, probably not one at all at this point in my life. But I know there is a power within us and without us that, sustained by belief, can work miracles in this world.

Most miracles are small and personal things: two people meeting and falling in love, a child’s face on Christmas morning when they find a dream come true, the birth on a winter’s night of a child entirely ordinary and no less miraculous. My Christmas wishes for myself and for my city may seem as improbable as the sentiments of a beauty contestant, but they’re not. My wish is for the thousand tiny and entirely human miracles I know are possible.

My wish is that at this holiday, somewhere in America, the separated parts of a family come together in exile--a little more complete—and begin their plans to go home; that somewhere in a line at a government office, two people discover that the other is not a greedy white boss or a scary black criminal, but someone with whom they share memories and hopes; that someone will come home today and, when the tears have finally stopped, they will begin again their life in New Orleans.

I'll see you there.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

The Dead

The New Orleans Times-Picayune reports today that the list of the missing in St. Bernard Parish has been reduced from over 200 to just 47. Sheriff Jack Stevens says deputies will begin searching in the surrounding marshes for those who may have been washed away.

At the cusp of the holidays, I imagine we should all be joyful to hear that over 150 people have been found alive, and I am. But I am also concerned at the thousands the most respected missing persons groups in this nation stil list as missing, and about what the St. Bernard outcome means for those still lost.

It means that at least 1,700 more people than the already reported 1,095 may be dead but undeclared by the government.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has reduced their list of missing children from over 1,000 to 508, but that is still an incredible number after four months. The same group's list of missing adults, last updated Dec. 19, still lists almost 4,800 missing adults.

As reported here on Nov. 1 and Oct. 4, the original list of the missing ran to over 7,000. I had previously suggested that the number of yet undeclared dead was over 1,000, based on a newspaper story reporting the results of resolving a Mississippi missing persons list (which found about 82% of the missing alive).

The results in St. Bernard, which are more likely to track those of New Orleans, found only 75% of the missing. The rest can't be accounted for, and the search for bodies in the marshes has begun.

For the entire Katrina and Rita disaster area, the original counts of over 7,000 would mean more than 1,700 dead are yet to be admitted by the government. The families of the unburied dead will not receive Social Security survivor benefits, or life insurance. Their estates will go unresolved, their families lives will never be healed.

I keep coming back to this because the so-called mainstream media will not touch this story. I sent all my research to a local journalist, who promised to look into it. How story ever came. Instead, we get this set in cold type: "List of Katrina missing reduced", with the upbeat subhead "Most in St. Bernard are confirmed alive".

As long as the government and the media try to pretend these people did not did, as long as Time Magazine does not correct it's statement about 23,000 acres devastated--when the figure is 23,000 square miles--I will keep writing here. I will not let them be forgotten.

Why are our leaders trying to suppress the death toll from the hurricanes and the failure of the defective levees? Why are the employees of Kenyon International Emergency Services charged with handling the dead, sworn to secrecy? Why was this company, a scandal-tainted Texas firm tied to the Bush family and implicated in illegally discarding and desecrating corpses, hired?

I believe I know why. It is clear that the death toll from the hurricanes, the flood, and the inept government response exceeds that of 9-11, probably by the hundreds. As I said back on All Saints' Day:

At the cusp of the holidays, I imagine we should all be joyful to hear that over 150 people have been found alive, and I am. But I am also concerned at the thousands the most respected missing persons groups in this nation stil list as missing, and about what the St. Bernard outcome means for those still lost.

It means that at least 1,700 more people than the already reported 1,095 may be dead but undeclared by the government.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children has reduced their list of missing children from over 1,000 to 508, but that is still an incredible number after four months. The same group's list of missing adults, last updated Dec. 19, still lists almost 4,800 missing adults.

As reported here on Nov. 1 and Oct. 4, the original list of the missing ran to over 7,000. I had previously suggested that the number of yet undeclared dead was over 1,000, based on a newspaper story reporting the results of resolving a Mississippi missing persons list (which found about 82% of the missing alive).

The results in St. Bernard, which are more likely to track those of New Orleans, found only 75% of the missing. The rest can't be accounted for, and the search for bodies in the marshes has begun.

For the entire Katrina and Rita disaster area, the original counts of over 7,000 would mean more than 1,700 dead are yet to be admitted by the government. The families of the unburied dead will not receive Social Security survivor benefits, or life insurance. Their estates will go unresolved, their families lives will never be healed.

I keep coming back to this because the so-called mainstream media will not touch this story. I sent all my research to a local journalist, who promised to look into it. How story ever came. Instead, we get this set in cold type: "List of Katrina missing reduced", with the upbeat subhead "Most in St. Bernard are confirmed alive".

As long as the government and the media try to pretend these people did not did, as long as Time Magazine does not correct it's statement about 23,000 acres devastated--when the figure is 23,000 square miles--I will keep writing here. I will not let them be forgotten.

Why are our leaders trying to suppress the death toll from the hurricanes and the failure of the defective levees? Why are the employees of Kenyon International Emergency Services charged with handling the dead, sworn to secrecy? Why was this company, a scandal-tainted Texas firm tied to the Bush family and implicated in illegally discarding and desecrating corpses, hired?

I believe I know why. It is clear that the death toll from the hurricanes, the flood, and the inept government response exceeds that of 9-11, probably by the hundreds. As I said back on All Saints' Day:

I believe they don’t want us to know how badly they failed us in New Orleans, just as they failed us in New York. If the truth were known, that as many and possibly more died in Katrina as died on 9-11, who would they have to blame?

They would have no one to declare war on but themselves.

Monday, December 19, 2005

Drowning in Stereotypes

Two of America's great newspapers ran stories with weekend on those who died in New Orleans as a result of the negligent failure of the federal levees after Katrina. The NYT article is a poignant tale of those who died, gleaned from records released to date by officials.

The LA Times story, Katrina Killed Across Class Lines, starts out to clear the air of stereotypes, then quickly descends into tossing those same cliches around like Mardi Gras beads. Worse, they miss the reallly import nuggest of data they are reporting on.

The LAT article looks at the neighborhoods destroyed by the collapse of the under-designed and poorly constructed levees, and starts out well. "[R]residents killed by Hurricane Katrina were almost as likely to be recovered from middle-class neighborhoods as from the city's poorer districts". But the article relies heavily on observations by Joachim Singelmann, director of the Louisiana Population Data Center at Louisiana State University, and Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella.

Campanella tells the LAT:

Mr. Campanella offers not indication of why he thinks elderly people are more likely to be wealthy. He may have been associated with Tulane University, but his daily commute must must involved airlifting in and out of the campus from some safe, gated community far away, to be able to make such a ridiculous assertion about the elderly of New Orleans.

The wealthy neighborhood Campanella and other in the stories mention is Lakeview. I was born into this neighborhood, but grew up in Lake Vista. My parents moved up to Lake Vista after they had "arrived", very much in the sense of the term arriviste. Until recently, the affluent moved North of Robert E. Lee Boulevard and left Lakeview behind them.

Most of those elderly residents of Lakeview had lived there their entire lives, had moved into the once modest suburb long before the builders of the late McMansions arrived on the scene. To suggest that, because they lived in company with the McMansion builders they were wealthy, is ridiculous, so it's not surprising that Campanella and the LAT offer no supporting data for this blithe assertion.

The LAT does point out that not everyone who died in the Ninth Ward was poor. They offer up one gentleman who "lived comfortably" but was moving out of the Ninth into Gentilly. What they missed is the well reported fact that the Ninth Ward had a home ownership rate higher than the rest of the city. In spite of the plague of crime and drugs that had come to it, the Ninth Ward was--like Lakeview once was--a place where working middle class people went to buy homes.

What the LAT means to say, but delicately and disingenuously avoids stating outright, is that it was not about race. I would agree to that proposition. It was, very much about class. The working class people of St. Bernard and the Ninth Ward died in much the same way. The elderly, generally not among the wealthiest citizens of our nation, died everywhere.

If this article sought to clear the air about who died and why in New Orleans, they missed the boat. Those who died were elderly, that is clear from the data. That some were affluent is mere speculation on their part, and I would offer my own thirty years observations in the city to counter that most were likely not.

Those who died were those without the means to readily evacuate, either due to age and infirmity or because they lacked the resources to pay for it. For the elderly and sick, the stories of their peers who died from the stress of evacuation before Hurricane Hugo gave them pause. They had lived through other storms, and better to gamble they would survive this one rather than die on the side of a highway.

Some stayed because they were told leaving early would cost them their jobs, which for someone hanging on to the edge of the middle-class, amounts to choosing between the risk of death and the certainty of poverty. When it because clear that they must go or risk death, it was too late. Others stayed because the entire store of wealth they had set aside in the world was their home, and in their drug and crime torn neighborhoods, they stayed behind to protect what little they had.

As another Tulane scholar, Elizabeth Furell, points out here, many were so rooted in New Orleans that had no extended social network of friends or family outside of the city to turn to when they could not find or afford a place to evacuate to. (This is exacerbated when my own relatively affluent and sophisticated family has a hard time finding a hotel, because so many people make two or three reservations when a storm threatens to ensure they have a convenient place to stay. Then, when others call, they find no room at the inn).

Those who stayed and died in Lakeview and in the Ninth Ward and in St. Bernard did so because most had no other real option.

The NYT article is a must read, cataloging the circumstances of those among the victims of the levee failures whose names were released by officials or by their families.

The NYT does its own statistical analysis, but more importantly, peers behind the numbers of who died and where to bring us the tales of how and sometimes why they died.

Read this article quick, before it disappears behind the subscription only/buy this article screen. Putting names and faces and circumstances on the statistics is too important to this story. Hell, if you missed it, drop my a line by the email link below and I'll send you a copy I saved off. If a national emergency frees the President from having to follow the law, then I feel free to disregard the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in response to the national emergency on the Gulf Coast.

The LA Times story, Katrina Killed Across Class Lines, starts out to clear the air of stereotypes, then quickly descends into tossing those same cliches around like Mardi Gras beads. Worse, they miss the reallly import nuggest of data they are reporting on.

The LAT article looks at the neighborhoods destroyed by the collapse of the under-designed and poorly constructed levees, and starts out well. "[R]residents killed by Hurricane Katrina were almost as likely to be recovered from middle-class neighborhoods as from the city's poorer districts". But the article relies heavily on observations by Joachim Singelmann, director of the Louisiana Population Data Center at Louisiana State University, and Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella.

Campanella tells the LAT:

Campanella said he was not surprised at the even distribution of bodies between the city's poorer and more affluent neighborhoods. He noted that 70% of the identified Katrina victims in New Orleans were older than 60, frequently lifelong residents who had ridden out other hurricanes and refused to evacuate. Elderly people are more likely to be wealthier and to live in wealthier neighborhoods.

Mr. Campanella offers not indication of why he thinks elderly people are more likely to be wealthy. He may have been associated with Tulane University, but his daily commute must must involved airlifting in and out of the campus from some safe, gated community far away, to be able to make such a ridiculous assertion about the elderly of New Orleans.

The wealthy neighborhood Campanella and other in the stories mention is Lakeview. I was born into this neighborhood, but grew up in Lake Vista. My parents moved up to Lake Vista after they had "arrived", very much in the sense of the term arriviste. Until recently, the affluent moved North of Robert E. Lee Boulevard and left Lakeview behind them.

Most of those elderly residents of Lakeview had lived there their entire lives, had moved into the once modest suburb long before the builders of the late McMansions arrived on the scene. To suggest that, because they lived in company with the McMansion builders they were wealthy, is ridiculous, so it's not surprising that Campanella and the LAT offer no supporting data for this blithe assertion.

The LAT does point out that not everyone who died in the Ninth Ward was poor. They offer up one gentleman who "lived comfortably" but was moving out of the Ninth into Gentilly. What they missed is the well reported fact that the Ninth Ward had a home ownership rate higher than the rest of the city. In spite of the plague of crime and drugs that had come to it, the Ninth Ward was--like Lakeview once was--a place where working middle class people went to buy homes.

What the LAT means to say, but delicately and disingenuously avoids stating outright, is that it was not about race. I would agree to that proposition. It was, very much about class. The working class people of St. Bernard and the Ninth Ward died in much the same way. The elderly, generally not among the wealthiest citizens of our nation, died everywhere.

If this article sought to clear the air about who died and why in New Orleans, they missed the boat. Those who died were elderly, that is clear from the data. That some were affluent is mere speculation on their part, and I would offer my own thirty years observations in the city to counter that most were likely not.

Those who died were those without the means to readily evacuate, either due to age and infirmity or because they lacked the resources to pay for it. For the elderly and sick, the stories of their peers who died from the stress of evacuation before Hurricane Hugo gave them pause. They had lived through other storms, and better to gamble they would survive this one rather than die on the side of a highway.

Some stayed because they were told leaving early would cost them their jobs, which for someone hanging on to the edge of the middle-class, amounts to choosing between the risk of death and the certainty of poverty. When it because clear that they must go or risk death, it was too late. Others stayed because the entire store of wealth they had set aside in the world was their home, and in their drug and crime torn neighborhoods, they stayed behind to protect what little they had.

As another Tulane scholar, Elizabeth Furell, points out here, many were so rooted in New Orleans that had no extended social network of friends or family outside of the city to turn to when they could not find or afford a place to evacuate to. (This is exacerbated when my own relatively affluent and sophisticated family has a hard time finding a hotel, because so many people make two or three reservations when a storm threatens to ensure they have a convenient place to stay. Then, when others call, they find no room at the inn).

Those who stayed and died in Lakeview and in the Ninth Ward and in St. Bernard did so because most had no other real option.

The NYT article is a must read, cataloging the circumstances of those among the victims of the levee failures whose names were released by officials or by their families.

The NYT does its own statistical analysis, but more importantly, peers behind the numbers of who died and where to bring us the tales of how and sometimes why they died.

Most victims were 65 or older, but of those below that age, more than a quarter were ill or disabled...almost three-quarters of the black victims examined by The Times and almost half the white victims lived in neighborhoods where the average income was below $43,000, the city's overall average. In New Orleans, the median income for whites is almost twice what it is for blacks. Many, if not most, were Louisiana natives, and virtually all were members of the working class - nurses, janitors, barbers, merchant marines.

Read this article quick, before it disappears behind the subscription only/buy this article screen. Putting names and faces and circumstances on the statistics is too important to this story. Hell, if you missed it, drop my a line by the email link below and I'll send you a copy I saved off. If a national emergency frees the President from having to follow the law, then I feel free to disregard the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in response to the national emergency on the Gulf Coast.

Saturday, December 17, 2005

Spirit, this is a fearful place

Two months ago, I posted a piece titled Ghost of New Orleans Future on what the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo's landfall at Charleston, S.C. meant for the future of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. The vision I saw was as bleak as the Dickensian title I chose for the piece, a city with a little crutch in the fireplace corner, without an owner.

Now, at the verge of Christmas, the Picayune discovers the example of Charleston, and couldn't be more please with what they find. I am instead reminded why I chose to echo the warning of Dicken's ghosts in The Christmas Carol, particularly the last of the spirits.

The T-P article A SISTER CITY FLOURISHES mostly gushes about how "the historic city demonstrated that a city can prosper if it takes care to keep its charm as it rebuilds."

A piece in Louisiana Weekly even earlier also looked to Charleston as a model for New Orleans' future. Charles Tidmore, who's become sort of a spokesman for New Orleans, found much to admire in the Charleston model.

But the Charleston outcome, while good for the few owners who homes became worth millions, is not one New Orleans should rush to emulate.

If you manage to wade through all of the T-P's boosterism, and make it to paragraph 50, you begin to hear hints that all is not wonderful in Charleston. According to the Picayune (and as reported covered by Wet Bank Guide two months ago):

As cited here in October, an article from Charleston's own newspaper, is less gushing about the outcome of Post Katrina, development.

This same article quotes Frederick Starr, who has written extensively about New Orleans and who has studied similar issues in New Orleans, said the changes are eating away at the life of the oldest neighborhoods in Charleston.

And the rest of New Orleans? What does Charleston tell us about the neighborhoods away from the beaten tourist path? Far, far down the Picayune article, it tells us

As I said in October, Charleston is not so much a model for New Orleans as a warning. If the Charleston model is followed, very few from here will be able to afford to live here. Those who return to labor in the tourism industry will return to homes more blighted than they knew before, to neighborhoods the invisible hand of recovery will pass over, or will be forced into far suburbs. The issues of New Orleans schools will at least be resolved, because families with children will be priced out of the market.

The historic city footprint will become a hollow shell, a Williamsburg farce for the people who keep homes there just for Mardi Gras. The people of Lakeview and Gentilly and New Orleans East, those who return, well perhaps they will have to consider moving to an affordable suburb, perhaps to the new development on the old Marcello family property of Churchill Farms, in a lovely KB Home.

I think a tone of Dickensian pessimism is appropriate if this is the future the publishers of the Picayune is offering us post-Katrina. The Ghosts of New Orleans Future remains essentially right: it is not the model for New Orleans, but a cautionary vision granted us by the spirits of the season. Ignore them at your peril.

Now, at the verge of Christmas, the Picayune discovers the example of Charleston, and couldn't be more please with what they find. I am instead reminded why I chose to echo the warning of Dicken's ghosts in The Christmas Carol, particularly the last of the spirits.

The T-P article A SISTER CITY FLOURISHES mostly gushes about how "the historic city demonstrated that a city can prosper if it takes care to keep its charm as it rebuilds."

Charleston today is a prosperous and vibrant place -- lively, swanky, immaculate. The antebellum houses, with their Palladian windows and long porches, are pristine, many without a flake of paint in sight. The old gardens are clipped and orderly with handsome brick walkways and well-bred hedges. Elegant church spires pierce a diminutive skyline. And King Street downtown -- narrow and intimate and architecturally vivacious -- is jammed with shops and shoppers.

In most parts of town, it would be hard to see any evidence that there was ever a hair out of place, never mind a disaster that rattled this city within an inch of its life.

By nearly every measure, the city is better than ever, stronger than it was before the storm.

A piece in Louisiana Weekly even earlier also looked to Charleston as a model for New Orleans' future. Charles Tidmore, who's become sort of a spokesman for New Orleans, found much to admire in the Charleston model.

But the Charleston outcome, while good for the few owners who homes became worth millions, is not one New Orleans should rush to emulate.

If you manage to wade through all of the T-P's boosterism, and make it to paragraph 50, you begin to hear hints that all is not wonderful in Charleston. According to the Picayune (and as reported covered by Wet Bank Guide two months ago):

The city has become richer and whiter. The suburbs have sprawled more. The historic districts are better preserved and gentrification is a constant threat to poorer neighborhoods. There are more tourists and fewer native-born residents.

As cited here in October, an article from Charleston's own newspaper, is less gushing about the outcome of Post Katrina, development.

Now, neighborhoods south of Broad Street and nearby face a more complex challenge: an influx of wealth so sweeping that it threatens to blur the difference between a living city and a museum.

Nancy Hawk has lived for decades at the southern end of Meeting Street, where tourists stroll among majestic homes.

The trouble is, many of those homes sit dark night after night.

"The houses are just empty. It's just depressing. It's sort of a deadening effect," she said. "It really does affect the feeling of being in a neighborhood, of actually being in a living community."

This same article quotes Frederick Starr, who has written extensively about New Orleans and who has studied similar issues in New Orleans, said the changes are eating away at the life of the oldest neighborhoods in Charleston.

"It becomes dead," he said. "If you really want these places to be around in another 300 years, it had better be a living place and not a dead museum

And the rest of New Orleans? What does Charleston tell us about the neighborhoods away from the beaten tourist path? Far, far down the Picayune article, it tells us

The city's East Side, a traditionally black neighborhood filled with handsome century-old architecture, has successfully resisted gentrification. But in the process it has also resisted restoration. It is one of the rare parts of town where the scars from Hurricane Hugo are still visible -- in boarded-up windows, crumbling porches and abandoned houses.

As I said in October, Charleston is not so much a model for New Orleans as a warning. If the Charleston model is followed, very few from here will be able to afford to live here. Those who return to labor in the tourism industry will return to homes more blighted than they knew before, to neighborhoods the invisible hand of recovery will pass over, or will be forced into far suburbs. The issues of New Orleans schools will at least be resolved, because families with children will be priced out of the market.

The historic city footprint will become a hollow shell, a Williamsburg farce for the people who keep homes there just for Mardi Gras. The people of Lakeview and Gentilly and New Orleans East, those who return, well perhaps they will have to consider moving to an affordable suburb, perhaps to the new development on the old Marcello family property of Churchill Farms, in a lovely KB Home.

I think a tone of Dickensian pessimism is appropriate if this is the future the publishers of the Picayune is offering us post-Katrina. The Ghosts of New Orleans Future remains essentially right: it is not the model for New Orleans, but a cautionary vision granted us by the spirits of the season. Ignore them at your peril.

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Laughter & disaster at the Humming Bird

Within hours of the Times-Picayune posting a story about a man who apparently committed suicide in Chris Owens's Bourbon Street nightclub, I received a joke on an email list out of New Orleans.

From my days as an ink stained wretch in the newspaper trade I recognized this immediately. It was the dark humor common to newsrooms, police stations, firehouses. It is the coping mechanism of people who look at tragedy daily, if not hourly; people who jobs don't allow them to turn away.

It reminded immediately of one memorable light night breakfast at the Humming Bird Grill. At an adjoining six-top were crewes of Emergency Medical Technicians, having their lunch break. One of them looked to be, maybe, eighteen years old. The grand old man of the group was attacking a huge platter of scrambled eggs, and describing to the new guy the suicide who took a header out of a downtown flophouse earlier in the evening.

"His brains were all over the place," he said as he hoisted a precariously full fork of eggs up to his mouth. "They looked like, well, kinda like his," he said, waving his fork around, "like scrambled brains." Into his mouth went the quivering yellow mass.

In my last year in the newspaper business, the shuttle Challenger exploded. I still remember that day clearly. I'd been stuck attending a Terrytown Rotary Club meeting to hear a politician ramble on about a subject I've long forgotten. The meeting broke up quietly after a waiter let the word into the room about the tragedy.

I hurried back to the office in Gretna, where we had a pathetic old black-and-white television connected to Cox Cable. In the early days of CNN, I saw the contrails, the explosion, the descending bits of the ship that held seven brave souls over and over and over again.

By the time I made it to the Abbey that night, I had an extensive repretiore of Christie McAuliffe jokes. It was what we did when confronted with horror. We were a select group, inured to tragedy, able to laugh at anything.

It was how one coped with a job that depends upon the tragedy of others. How else do you handle being sent out to try and collect a photograph of the tragic teenage traffic fatality from his grieving parents, with the remains of a plane scattered where a day care center once stood, with the stuff of news.

Now, everyone in New Orleans is in on the secret. You don't have to spend your nights in a squad car or ambulance, or chase them with a scanner. Katrina has created a tragedy of proportions not seen in this country since the Civil War. Thousands dead, hundreds of thousands of homes destroyed, 23,000 miles devastated (not acres, as misreported by Time magazine) .

Three months later, the thin barrier island between the river and the back swamp that makes up New Orleans today is full of people who've made it back home, or who've never left. They can buy a newspaper and a cup of coffee, can go out to lunch or dinner. I saw a report that retailers on Magazine are looking at a banner year, their best in a long time. Life, for some, is something superficially normal.

But no one back in New Orleans can escape what lurks less than a mile away from any of them. A city in ruins. The catastrophe of storm and flood are the elephant in every room, the unspoken obscenity in every conversation, the invisible stain on everything in view.

I don't live in New Orleans now. I can only glean what it is like from conversations with or emails and blog posts from friends and acquaintances. But I know living in New Orleans now is difficult beyond anything other Americans can imagine, because nothing like this has happened in America before.

Still, if you've got a home to repair or a job to go to, you have to get up and get out and cope. And people who would have been shocked by it only a few months ago are discovering the secret release of gallows humor.

I wasn't distressed to receive the joke about the suicide at Chris Owens. I was surprised it had taken so long to get one.

There was a suicide last night at Chris Owens bar.

Some are saying she will name a new drink, The Head Shot.

From my days as an ink stained wretch in the newspaper trade I recognized this immediately. It was the dark humor common to newsrooms, police stations, firehouses. It is the coping mechanism of people who look at tragedy daily, if not hourly; people who jobs don't allow them to turn away.

It reminded immediately of one memorable light night breakfast at the Humming Bird Grill. At an adjoining six-top were crewes of Emergency Medical Technicians, having their lunch break. One of them looked to be, maybe, eighteen years old. The grand old man of the group was attacking a huge platter of scrambled eggs, and describing to the new guy the suicide who took a header out of a downtown flophouse earlier in the evening.

"His brains were all over the place," he said as he hoisted a precariously full fork of eggs up to his mouth. "They looked like, well, kinda like his," he said, waving his fork around, "like scrambled brains." Into his mouth went the quivering yellow mass.

In my last year in the newspaper business, the shuttle Challenger exploded. I still remember that day clearly. I'd been stuck attending a Terrytown Rotary Club meeting to hear a politician ramble on about a subject I've long forgotten. The meeting broke up quietly after a waiter let the word into the room about the tragedy.

I hurried back to the office in Gretna, where we had a pathetic old black-and-white television connected to Cox Cable. In the early days of CNN, I saw the contrails, the explosion, the descending bits of the ship that held seven brave souls over and over and over again.

By the time I made it to the Abbey that night, I had an extensive repretiore of Christie McAuliffe jokes. It was what we did when confronted with horror. We were a select group, inured to tragedy, able to laugh at anything.

It was how one coped with a job that depends upon the tragedy of others. How else do you handle being sent out to try and collect a photograph of the tragic teenage traffic fatality from his grieving parents, with the remains of a plane scattered where a day care center once stood, with the stuff of news.

Now, everyone in New Orleans is in on the secret. You don't have to spend your nights in a squad car or ambulance, or chase them with a scanner. Katrina has created a tragedy of proportions not seen in this country since the Civil War. Thousands dead, hundreds of thousands of homes destroyed, 23,000 miles devastated (not acres, as misreported by Time magazine) .

Three months later, the thin barrier island between the river and the back swamp that makes up New Orleans today is full of people who've made it back home, or who've never left. They can buy a newspaper and a cup of coffee, can go out to lunch or dinner. I saw a report that retailers on Magazine are looking at a banner year, their best in a long time. Life, for some, is something superficially normal.

But no one back in New Orleans can escape what lurks less than a mile away from any of them. A city in ruins. The catastrophe of storm and flood are the elephant in every room, the unspoken obscenity in every conversation, the invisible stain on everything in view.

I don't live in New Orleans now. I can only glean what it is like from conversations with or emails and blog posts from friends and acquaintances. But I know living in New Orleans now is difficult beyond anything other Americans can imagine, because nothing like this has happened in America before.

Still, if you've got a home to repair or a job to go to, you have to get up and get out and cope. And people who would have been shocked by it only a few months ago are discovering the secret release of gallows humor.

I wasn't distressed to receive the joke about the suicide at Chris Owens. I was surprised it had taken so long to get one.

Thursday, December 08, 2005

Meet the Boys on the Battle Front

Meet the boys on the battle front.

Meet the boys on the battle front.

Meet the boys on the battle front.

Oh, the Wild Tchoupitoulas gonna stomp some romp.

--The Wild Tchoupitoulas

Like two tribes of rival Mardi Gras Indians, the forces for and against Mardi Gras 2006 are spying each other out and getting ready for battle.

The conflict pits the traditional boosters of Mardi Gras, the parading krewes and the city’s tourism industry, against some of the people of New Orleans who are more worried about when they might be able to return to their homes, or if there will be jobs and schools for them if they do.

The man who speaks for mainstream Mardi Gras, Mardi Gras Guide publisher Arthur Hardy, spoke up less than a week after the hurricane and levee failure, calling on Sept. 6 for carnival to go on.

Hardy, who has been publishing his guide for 30 years and is one of the foremost experts on Mardi Gras, [told WWL-TV] next year's celebration is also important because it's the 150th anniversary of the first formal parades in the city.

"I've heard some people say we can't do it," Hardy said. "But it's a very significant anniversary and I can't imagine it going unmarked without some kind of parade. It's in our soul to have Mardi Gras."

The Informants carried the first news of possible trouble when the subject of Mardi Gras was first broached in September by Mayor Ray Nagin, still only a few weeks after Hurricane Katrina devestated 23,000 square miles of teh Gulf Coast, and laid much of New Orleans to waste.

Following November meetings between city officials and representatives of the parading Krewes, a six-day schedule of parades was proposed by Nagin hether

Immediately, some critics charged the city could not afford to spend time and money on Mardi Gras when ninety percent of the city was in ruin. At the same time, the Krewes were disappointed that Nagin was proposing such an abbreviated season, suggesting that the celebration was too important both to New Orleanians and to the local economy, to curtail it so significantly. Nagin ultimatley relented and extended the window to eight days, to include two weekends so more krewes might be able to parade.

Then the city's premiere black Mardi Gras organization, Zulu, threatened not to parade unless they were allowed to follow their traditional route, which includes runs through predominately black neighborhoods on Claiborne, Orleans and Galvez.

Mardi Gras has long been a sore spot in race relations in the city. With the exception of Zulu, krewes are largely clubs for the white middle and upper class. If the New Orleans of the future is to be a better city, I think not only should Zulu be allowed to follow their traditional route, but that Rex should show his royal face on Claiborne and Orleans and Galvez Avenues.

But the real trouble was still out on the Front, far away from the Big Chief. The two tribes first clashed when Mayor Nagin traveled to Atlanta, GA for one of a series of town hall meetings with displaced residents.

On Dec. 3, angry Katrina survivors told Nagin they didn't think the city should be spending scarce funds on the police and sanitation costs of carnival.

"How can we be having Mardi Gras and we aren't even there?" Gaynor said, adding that it was a shame to have such a celebration in the wake of so many lives lost and so much uncertainty," displaced New Orleans resident Betty Gaynor told Nagin at this town hall meeting in Atlanta.

This one small paragraph turned into a firestorm. Some of the critics are planning demonstrations against the idea when the New Orleans Saints travel to Atlanta on Dec. 12 for a Monday Night Football game against the Falcoms.

[M]any community activists — particularly leaders of poor, black neighborhoods that were destroyed by the floodwaters and have sat virtually untouched ever since — have turned against the idea, the Los Angeles times reports.

"We're not against Mardi Gras. We're against their priorities," ChiQuita Simms, a displaced New Orleans resident who is organizing a protest, said of city leaders

But white Mardi Gras' Wild Man Hardy asked in another Times-Picayune article, "If we canceled Mardi Gras, would anyone who's homeless suddenly have a home? Would the levees be rebuilt? We can't erase Katrina simply by erasing the celebration."

That same article outlines how corporate sponsortship, long a taboo in carnival, would be allowed to help get the krewes rolling again. No advertising would be allowed on floats, and the branding seen on college football bowl games would not be allowed.

The opponents in Atlanta, mostly black and working class, are people from the same communities that spanwed the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. Sadly, with the current lack of housing and jobs and schools, particularly in the Indian's own neighborhoods, it is likely that this key part of carnival may be sadly reduced come Feb. 28, 2007.

But as I reported in late September some tribes are promising to be back. The Wild Magnolias, (like the Wild Tchoupitoulas

On their web site, Big Chief Bo Dollis promised "We'll be back for Mardi Gras 2006, with brand new suits!"

Hey-pocky-way!

Monday, December 05, 2005

Port President to N.O. -- We don't need you

Gary P LaGrange, president of the Port of New Orleans, told the Los Angeles Times in a Dec. 3 story that "[the port]" doesn't need the city."

On Page 2 of the online version, when asked about "inferences that the city is equally important" in the Times' words, LaGrange said, "That's bull."

Strangely, the port's own web site boasts that there are 60,000 people directly employed in the maritime industry, and that the the port is responsible for more than 107,000 jobs.

If Mr. LaGrange doesn't feel a city is needed, how precisely does he propose to hire these workers? Perhaps he is considering replacing the port's workers with illegal aliens, and housing them in tents and storm-damaged buildings with no utilities or running water, a popular solution for some local business.

Mr. LaGrange also says that "New Orleans is the biggest throughput port in the country. It doesn't need the city. the value added here is very minimal."

Again, the Port's own website boasts of the extensive coffee industry, with "six roasting facilities in a 20 mile radius". It also talks about the port's extensive inter-modal facilities, for transferring cargo from ship to barge or rail or truck.

Perhaps he thinks this cargo can transfer itself, and that the coffee can roast and package itself, if there is no city and therefore are no workers.

Mr. LaGrange should be canned from his port position immediately, and asked to leave the city. If he doesn't wish to leave the city voluntarily, there are some ancient southern traditions involving split rails, hot tar, and feathers to which he should be introduced. The city is badly in need of a parade.

He is clearly unsuited to a position of responsibility during the post-Katrina reconstruction of New Orleans. Perhaps former FEMA chief Micheal Brown can offer him a new job in his disaster response consultancy.

On Page 2 of the online version, when asked about "inferences that the city is equally important" in the Times' words, LaGrange said, "That's bull."

Strangely, the port's own web site boasts that there are 60,000 people directly employed in the maritime industry, and that the the port is responsible for more than 107,000 jobs.

If Mr. LaGrange doesn't feel a city is needed, how precisely does he propose to hire these workers? Perhaps he is considering replacing the port's workers with illegal aliens, and housing them in tents and storm-damaged buildings with no utilities or running water, a popular solution for some local business.

Mr. LaGrange also says that "New Orleans is the biggest throughput port in the country. It doesn't need the city. the value added here is very minimal."

Again, the Port's own website boasts of the extensive coffee industry, with "six roasting facilities in a 20 mile radius". It also talks about the port's extensive inter-modal facilities, for transferring cargo from ship to barge or rail or truck.

Perhaps he thinks this cargo can transfer itself, and that the coffee can roast and package itself, if there is no city and therefore are no workers.

Mr. LaGrange should be canned from his port position immediately, and asked to leave the city. If he doesn't wish to leave the city voluntarily, there are some ancient southern traditions involving split rails, hot tar, and feathers to which he should be introduced. The city is badly in need of a parade.

He is clearly unsuited to a position of responsibility during the post-Katrina reconstruction of New Orleans. Perhaps former FEMA chief Micheal Brown can offer him a new job in his disaster response consultancy.

Saturday, December 03, 2005

Child of Desire

This unsigned panel was the sole surviving piece of a student mural at Desire Street Academy, part of Desire Street Ministries. Photo courtesy of Steve Crow, who took this while volunteering in the area. I think this speaks of Katrina and New Orleans in a way nothing else I have seen can approach.

Until you understand this panel, there's is nothing that George Rodrigue's Blue Dog or displays of Toxic Art can do to save you. You first have to understand the despair the people of the Dome and Convention Center sometimes knew long before Aug. 28. You have to understand the despair of coming home to a ruined home on a wasted street in a neighborhood destroyed. You have to understand the despair of watching America abandon the city, hundreds of thousands of it citizens. You have to understand that New Orleans is on it's own.

Until this young man and everyone like him can lift up their faces and stand and take the first steps toward the future, there will be no recovery. It doesn't matter if those steps are taken in New Orleans or Houston or Atlanta, there will be no healing until he and all like him are healed.

There will be no rebuilding until this artist comes home to stay, and a decade from now takes his children down to the 'hood to see this piece once again mounted. There will be no recovery until he can stand before this and say, proudly, I made that, out of this place and the life of this place, just like I made the house you live in and the life you have in this city, just like I made you someone who can be proud, living in a place to be proud of. Out of despair you can make something beautiful.

Friday, December 02, 2005

A Second Reconstruction

Pennies on the dollar.

That's what U.S. Rep. Richard Baker thinks the homes of New Orleans and other Katrina survivors are worth. At least, that's what legislation he is proposing would offer them as a "buy out" for ruined homes.

Homeowners, many of whom had no flood insurance because the FEMA flood maps told them it was unnecessary, may have no choice but to take an offer to buy them out from under their mortgages, surrendering their equity, their homes, their lives in the process. The ninety-day moratorium on mortgage payments ends in December, and the owners of ruins will be required to resume payments, and make up the last three months.

Optimistic suggestions that homes in flood-ravaged neighborhoods, particularly those that are candidates for being red-lined in do not rebuild zones, be paid for at something like pre-Katrina values appear to have been a fantasy.

When Mayor Ray Nagin suggested weeks ago in a long Times-Picayune interview that people should at least be compensated at their pre-storm tax assessments--something of a joke in a town with elected property assessors who routinely undervalue property--people were upset that they would not be fairly compensated.

When the Urban Land Institute proposed that large areas of the city be redlined against immediate redevelopment, there was predictable outrage. But among the many recommendations the group made, one was for buyout of ruined homes at pre-Katrina values.

I criticized the ULI plan for a redevelopment corporation for placing control of the reconstruction in the hands of outsiders. Baker's plan would not even provide the local or state government with appointees to his Louisiana Recovery Corporation. Instead, the President would appoint all of the members.

The article that started this posting points out that Baker has yet to find a single cosponsor for his plan among his own party, the Republicans. The GOP, however, has made it clear that they have no plans to surrender a penny of their tax cuts or rich pork to spend on Gulf Coast recovery.

Baker has made overtures to the Congressional Black Caucus, which has it’s own recovery plan. It is a reasonable and appropriate proposal, including a 9/11-like victim restoration fund, health benefits for evacuees, tax credits up to $5,000 per family, an exemption for victims from bankruptcy and $50 million to ensure that evacuees can vote absentee.

Sadly, both Nagin and Governor Kathleen Blanco have ignored the efforts of the Black Caucus. Both forgot their own calls for real Federal assistance, and instead endorsed Baker's plan. It is an admission of defeat.

Unlike the victims of 9-11, who were all compensated for their losses out of a fear that lawsuits would bring about the collapse of the airline and insurance industries, the people of Katrina will receive pennies on the dollar, and a promise of first crack at any redeveloped property.

They are not, in the equations of the people in power, worth as much as the people of New York, not worth even as much as the busboys of the restaurant atop the twin towers.

What the Gulf Coast if facing is a second reconstruction. The first was purportedly about eradicating the plantation-and-slave culture of the south after the Civil War. It was, instead, an exercise in organized pillage and looting by the victors.

Katrina may have been an act of God and not an act of war, but people who have whetted their appetites on the rich contracts of the war on terror are not about to pass up an opportunity to profit wherever misfortune presents an opportunity.

So, the people of Katrina will be bought out from under their mortgages, losing all their equity, and their banks will be forced to take partial payment on their mortgages. And then the devastated land—23,000 square miles of the United States was ravaged by the storm---will be packaged for resale to developers.

The nation of the greatest generation is gone. The nation that mobilized millions to wage a war against evil that spanned the globe, and went on to rebuild all of Europe and Asia, that nation is just a memory, just another program on the History Channel. If we cannot save the Gulf Coast, then we are not longer a nation capable of great things.

Instead, we are a nation that cannot pay it’s bills, much less afford to rebuild the Gulf Coast. Our president is off doing his best imitation of Mussolini invading Ethiopia, and has forgotten his promises of September. Our members of congress are busy defending the tax cuts for their contributors and their pork barrel projects against any claims of the survivors of Katrina.

Welcome to the Second Reconstruction. In the first, the white population of the post-war South was pillaged of what little they had left at the end of that terrible and pointless war. The former slaves were promised freedom and the vote and 40 acres and a mule. Both communities came away destitute, and the former slaves were betrayed.

What everyone got instead was the enrichment of the carpetbaggers and scalawags, and a culture of corruption in government that enriched those in power. The rest got institutionalized poverty and racism.

Welcome to the second Reconstruction.

That's what U.S. Rep. Richard Baker thinks the homes of New Orleans and other Katrina survivors are worth. At least, that's what legislation he is proposing would offer them as a "buy out" for ruined homes.

Homeowners, many of whom had no flood insurance because the FEMA flood maps told them it was unnecessary, may have no choice but to take an offer to buy them out from under their mortgages, surrendering their equity, their homes, their lives in the process. The ninety-day moratorium on mortgage payments ends in December, and the owners of ruins will be required to resume payments, and make up the last three months.

Optimistic suggestions that homes in flood-ravaged neighborhoods, particularly those that are candidates for being red-lined in do not rebuild zones, be paid for at something like pre-Katrina values appear to have been a fantasy.

When Mayor Ray Nagin suggested weeks ago in a long Times-Picayune interview that people should at least be compensated at their pre-storm tax assessments--something of a joke in a town with elected property assessors who routinely undervalue property--people were upset that they would not be fairly compensated.

When the Urban Land Institute proposed that large areas of the city be redlined against immediate redevelopment, there was predictable outrage. But among the many recommendations the group made, one was for buyout of ruined homes at pre-Katrina values.

I criticized the ULI plan for a redevelopment corporation for placing control of the reconstruction in the hands of outsiders. Baker's plan would not even provide the local or state government with appointees to his Louisiana Recovery Corporation. Instead, the President would appoint all of the members.

The article that started this posting points out that Baker has yet to find a single cosponsor for his plan among his own party, the Republicans. The GOP, however, has made it clear that they have no plans to surrender a penny of their tax cuts or rich pork to spend on Gulf Coast recovery.

Baker has made overtures to the Congressional Black Caucus, which has it’s own recovery plan. It is a reasonable and appropriate proposal, including a 9/11-like victim restoration fund, health benefits for evacuees, tax credits up to $5,000 per family, an exemption for victims from bankruptcy and $50 million to ensure that evacuees can vote absentee.

Sadly, both Nagin and Governor Kathleen Blanco have ignored the efforts of the Black Caucus. Both forgot their own calls for real Federal assistance, and instead endorsed Baker's plan. It is an admission of defeat.

Unlike the victims of 9-11, who were all compensated for their losses out of a fear that lawsuits would bring about the collapse of the airline and insurance industries, the people of Katrina will receive pennies on the dollar, and a promise of first crack at any redeveloped property.

They are not, in the equations of the people in power, worth as much as the people of New York, not worth even as much as the busboys of the restaurant atop the twin towers.

What the Gulf Coast if facing is a second reconstruction. The first was purportedly about eradicating the plantation-and-slave culture of the south after the Civil War. It was, instead, an exercise in organized pillage and looting by the victors.

Katrina may have been an act of God and not an act of war, but people who have whetted their appetites on the rich contracts of the war on terror are not about to pass up an opportunity to profit wherever misfortune presents an opportunity.

So, the people of Katrina will be bought out from under their mortgages, losing all their equity, and their banks will be forced to take partial payment on their mortgages. And then the devastated land—23,000 square miles of the United States was ravaged by the storm---will be packaged for resale to developers.

The nation of the greatest generation is gone. The nation that mobilized millions to wage a war against evil that spanned the globe, and went on to rebuild all of Europe and Asia, that nation is just a memory, just another program on the History Channel. If we cannot save the Gulf Coast, then we are not longer a nation capable of great things.

Instead, we are a nation that cannot pay it’s bills, much less afford to rebuild the Gulf Coast. Our president is off doing his best imitation of Mussolini invading Ethiopia, and has forgotten his promises of September. Our members of congress are busy defending the tax cuts for their contributors and their pork barrel projects against any claims of the survivors of Katrina.

Welcome to the Second Reconstruction. In the first, the white population of the post-war South was pillaged of what little they had left at the end of that terrible and pointless war. The former slaves were promised freedom and the vote and 40 acres and a mule. Both communities came away destitute, and the former slaves were betrayed.

What everyone got instead was the enrichment of the carpetbaggers and scalawags, and a culture of corruption in government that enriched those in power. The rest got institutionalized poverty and racism.

Welcome to the second Reconstruction.

"And when we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard nor welcome, but when we are silent we are still afraid. So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive." -- Audie Lorde

Any copyrighted material presented here is done so for the purposes of news reporting and comment consistent with USC 17 Chapter 1 Title 107.