Friday, March 31, 2006

We Are Not OK

The newspapers don't tell us, because it was not an exceptional occurrence. As the headline moved by the Reuters News Agency summaries, Grim Find Shows Normalcy Still Eludes New Orleans.

We are not OK.

S.O.S. Katrina We Are Not OK is one of my favorite blog titles, and blogger Dangle's everyman chronicle of the disaster is a compelling view into not just the disaster, but one locals' visceral reaction to it. Almost everyone who blogs about New Orleans has made it their theme at one point or another, although I have not. What they try to say, in their particular stories of it all, is that we are not OK>

New Orleans author and blogger Poppy Z. Brite took up this same theme this week in an online community, offering her own summary of why We Are Not OK.

Occasionally I'm asked by friends Not From Here, "New Orleans is better now, right? You had Mardi Gras!" or "Are you doing OK?" or some variation. Sometimes, particularly if they're contemplating a visit, I even try to reassure them: it's very possible to have a good, safe time here; the French Quarter is fine; lots of restaurants and bars are open. In truth, though, New Orleans and most of its inhabitants are very much Not OK. I present to you a baker's dozen facts about life in the city seven months after the storm. Some are large, some small. I think many of them will surprise you...No, we are not OK, New Orleans is not OK. It is a disaster zone after seven months. The current 200,000 residents are the walking wounded, many with a dangerously glassy eyed disconnection, others erupting routinely in anger. Those not crammed into tiny apartments or several families to a house on the Island--the sliver by the river of high land--are camping in the ruins of gutted homes without electricity or potable water. Another several hundred thousands remained scattered around the country with their lives in tatters. In Calcasieu parish there are still people living in tents. Mississippi along the coast is not much different from the pictures the world saw of the tsunami of Xmas 2004.

I am still living 1,200 miles away, and don't find much time as a single parent packing a house up to go to chitchat with people about New Orleans, or my imminent move back . Few ask why I would move back, and it surprises me. I take it to mean that they think things on the coast really are OK, that New Orleans is getting back to normal.

Things are not getting back to normal. I no longer read my local paper, except as I take copies and crumble pages into boxes and around things to move, but I read the Times Picayune on line every day. I know I am moving home to a place where the levees may or may not hold in the next storm, where homeowners insurance rates are skyrocketing if you can even get insurance, where the price of a dry home is almost ruinous, where because the government refuses to offer the same aid to the local utility they gladly gave ConEd after 9-11 I worry how we might pay a utility bill that could double what they were in the past.

I am taking my family, including my children, to a city over half of which is an empty wasteland of ruined homes, dark as the country at night because much of the city has no electricity, where the U.S. Government after seven months has not re-established reliable mail service even to the dry and secure parts of town, where garbage collection is not a routine but a cause for neighborhood celebration.

Why? I want people to ask me, why would I do this? I am going because we are not OK. And I am going because you don't ask anymore, whether you just don't want to know or because you have heard we are OK.

I am going home because the central government is trying to turn us into a needy interest group, and turn their back on their obligation to aid us, because it increasingly looks like we will be on our own. Remember that the vast majority of damage in New Orleans was the result of the failure of levees the Corps of Engineers, which knew were substandard and not up to the task. Because we have such a clear claim upon billions in compensation the government don't wish to pay, they must turn us into a something alien and undeserving.

We are not. Members of needy welfare groups don't work eight hours a day then return to a home that is bare studs inside to spend another six or eight hours working on their ruined homes by lantern light. They don't stand in line for hours to collect their mail so they can pay their bills on time because the post office won't resume regular deliveries, or spend their free time cleaning the parks and boulevards (we call them "neutral grounds"), or helping the elderly clean out their homes.

Needy welfare dependents don't willing go into the stink and the ruin in a place where one routinely finds the decayed remains of the dead.

These people are of a kind that the descendants of the hardy pioneers of North Dakota, where I now live, should understand. I am going because I have to be with them. I have to do what I can to save my city, the city I grew up in, the only city of a half dozen I've lived in that I've ever loved. I have to go to help prove that southerners in general and Orleanians in particular are not the grasshoppers among the American ants; we are the people who rebuilt after the civil war, the flood of 1927, the terrible hurricanes of the past.

I am going home to live among people who know that we are not OK. Every week, I hear or read something that cause me to boil up in a paroxysm of anger. This week's installment occurred when a local United States Senator announced an aid package for farmers, telling the local media that if we were spending billions on the Gulf Coast, we must not forget the farmers in North Dakota. Every county in the state was declared a disaster area at some point last year, he reminded us, and they want their cut of the money.

Disaster? I shouted out at the radio, pounding on the steering wheel. How could he dare compare the annual routine of too much or not enough rain, of wind and hail to what happened to the Gulf Coast? How many bodies did they pull out of homes last week in North Dakota, Senator? How many people are still living in tents or tin trailers seventh months after their "disaster"? Is half the population of your state (about the same size as the population of pre-flood New Orleans) living in another state, everything they own lost and owing a mortgage on a ruined home for which insurance will not pay? How many people are suffering traumatic stress disorder? One hundred thousand? Two hundred thousand?

Calm down, I reminded my self. Breathe. I went home and furiously packed boxes, in the adrenaline frenzy I had long ago when I dropped my motor bike on the Greater New Orleans Bridge and was almost run over by a semi, then went home and painted half my apartment in a night.

I'm not just angry at clueless congressmen from far away. I'm angry at our own, at our clueless mayor who turned away a bid to pay the city to haul away the tens of thousands of ruined cars in favor of one that will cost tens of millions, on the theory that FEMA would reimburse us. I'm angry at the Archdiocese of New Orleans, which sent armed guards into a mass at the city's (perhaps the nation's) oldest parish founded by blacks, to protect their not very popular spokesman and an out of parish priest from parishioners who sat in the pews holding protest signs and singing We Shall Not Be Moved to protest the closing of their parish.

We are not OK.

I need to live among people who know we are not OK, people who share the same anger and despair. I need to find a way to turn that anger into energy to rebuild a city, a culture, a way of life. That's why I'm going back to live just blocks from vacant neighborhoods of rubble and ruin. If I were to stay in Fargo, the anger and frustration will surely kill me.

Not everyone can go home. We have the resources (just barely) to afford it. My children are bright enough to get into the decent magnet or charter schools in a city where the school system was a disaster before the flood. We don't have a mortgage on a slab that was once a home hanging over our heads.

The people who are scattered from Austin to Atlanta, the ones who can't go home because they cannot afford it, because their jobs in New Orleans were lost with their homes and everything they owned, or because they are afraid, you need to tell your new neighbors and co-workers: we are not OK.

We need to tell everyone who will listen that this is not an abstract fight over how many zeroes can dance on the crown of a pinheaded appropriations committee member, that we are not just another needy interest group begging for money, this is not a debate over whether we shall or shall not have a new Super Wal-Mart in our neighborhood. It is a battle for the soul of our city, and a battle for the soul of America.

We are not OK, but tens of thousands more are coming home each month anyway--evacuees and ex pats alike. We are coming home to save the soul of our city, to do what we can to ensure a unique way of life and three hundred years of history are not lost to neglect or Disney-inspired "redevelopment". We are coming home knowing the rest of America seems unprepared to pay the cost, ready to do it alone if we must.

We can't save the soul of America. Only the rest of the country can do that. If they turn their back on New Orleans, if they refuse to pay the just compensation for the criminal negligence of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, if they deny us the same aid they gladly offered New York a few short years ago, if they won't pay the cost of the denuding our coast for a navigable river and our oil-and-gas, then the soul of America will be lost.

I can't blame you if you have disaster fatigue. Every day the newspaper brings another tail of woe. Thousands die when an earthquake collapses their ancient brick homes, a creaking wooden ferry overturns somewhere at sea and everyone drowns. It's almost too much to contemplate. Perhaps the cult of LaHaye is right, and the end is nigh.

Before your turn the page, think about this: New Orleans is not OK. We are not OK. And we are not discussing some distant, benighted village in the hills of Afghanistan or on the coast of Africa or Asia. We are talking about your neighbors--not just that your fellow Americans, but right in your own town. There is not a significant city or town in America that isn't hosting some cohort of the displaced. You pass us every day on the street, but perhaps you don't recognize the despair or the anger that squeezes at our hearts like an angry fist.

Know this: we are not OK. We will rebuild, with or without your help. We will, if we must, save ourselves. Whether your come to our aid as all honor and justice and charity demands will determine if you can save yourselves.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Post-Katrina looting continues

FEMA Abandons Pledge on 4 No-Bid Contracts

The second tier of subcontractors is equally as corrupt, as we have explored in past posts. It's clear that the entrenched culture of corruption in Washington makes them unfit to handle the significant taxpayer dollars involved.WASHINGTON - FEMA has broken its promise to reopen four multimillion-dollar no-bid contracts for Hurricane Katrina work, including three that federal auditors say wasted significant amounts of money...

A review by Government Accountability Office of 13 major contracts said last week the government had wasted millions of dollars, due mostly to poor planning by FEMA. Among the 13 were three of the four no-bid contracts for temporary housing, worth up to $500 million each, that went to three major firms with extensive government ties...The Shaw Group's lobbyist, Joe Allbaugh, is a former FEMA director and friend of President . Bechtel CEO Riley Bechtel served on Bush's Export Council from 2003-2004, and CH2M Hill Inc. and Fluor Corp. have done extensive previous work for the government...

It's important that we take local control of the revenue from oil-and-gas activity in the Gulf, so that the recovery process can be funded locally and taken out of the hands of Washington looters. Washington has no stake in the recovery of Gulf Coast. They have their contracts, and are skimming the recovery dollars as fast as they can. The port is open and oil-and-gas production is largely restored. Mission Accomplished.

Meanwhile the better part of a million Americans remain displaced, some still living in tents. Vast swaths of the United States--covering 23,000 square miles--remain in ruins. Mail service has not been restored after six months. No one has a higher stake in seeing recovery dollars spent wisely than the people of the Gulf Coast.

It's time to end the looting.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers looting culture of corruption

Monday, March 27, 2006

A howling in the wires

By Tuesday Aug. 29, it was clear that New Orleans did not "dodge the bullet". Instead, the greatest disaster in the history of the United States began to unfold. I was hypnotised. Where I couldn't get through the work firewall to get the news I wanted, I yanked the fax machine cord out of the wall and hooked up my laptop.

I realized that hundreds of thousands of my former neighbors were displaced by evacuation, and would be hungry for information. As a former newspaper reporter and editor, I know that I could do something for them, and began this blog.

One of my earliest posts was this:

I wasn't the only person blogging New Orleans.I've been aggregating news from NOLA for numerous online forums I participate in over the last two days. I'm going to concentrate my efforts here instead, to help the new Katrina diaspora keep up with what's happening to our city.First, the cable news networks are behind on the story, and are often flatly contradicted by local sources. I recommend those (and will list them in a separate post) if you prefer to go straight to the source.

I named this blog for my old newspaper, the West Bank Guide, where I once slaved as an ink-stained wretch in the 1980s. I also worked in New Orleans East and St. Bernard Parish for the same outfit, and the pictures I see of those areas are just devastating.

Scores of new blogs popped up in the following weeks. Some were absolutely compelling, such as the Interdictor, which was blogging live from NOLA via a hardened ISP site. Others were expats like myself, who felt compelled to tell the world a truer story of what was happening that the national media, with all their resources, could apparently manage.

The outpouring of words was a howling in the wires, an electronic echo of the sound everyone who's been through a big storm knows. Even as the sound died in the last of the wires sagging from the akimbo poles in New Orleans, our own howling continued: a banshee wail for the dead not yet reported, a war whoop against those would would not protect or rescue, a keening for the city dying before our eyes that still reverberates today like the microwave hum of the big bang that fills the universe.

The work continues, as the city struggles more than six months later. Bloggers continue to lead the major media on key stories such as federal relief funding and housing issues. On bad days they pour out their anguish over the struggle. On good days they share their dreams for a better city. Much of the best writing and reporting about the city never makes it into the traditional media. It appears on line.

Now blogger Alan Gutierrez of Think New Orleans asks NOLA bloggers to participate in an experiment in "viral linking", a way for bloggers to call out each other's work and build readership. I think it's a grand idea, precisely because so much good work is being done by the blogging community. And this howling in the wires will not end in our lifetimes. It will take that long to rebuild New Orleans, and I think that those of us who write about the place will have work to do, stories to tell, angst to unload until the nursing home cuts off our computer privileges.

So to answer Alan's call for a Link Think New Orleans campaign, I want to call out some people who don't pop up anywhere near the top of the Technorati heap, but should. First is New Orleans Blogger Kinch. If you aren't reading this architect's blog Rebuilding Big Easy you're missing out on some of the most important stories about how the city will or can be rebuilt. The article behind the tag is the one that started the NOLA blogosphere on the Katrina Cottage story. (Katrina Cottage is still the most frequent Google Search that bring people to Wet Bank Guide.

It's hard to pick my second. There are a lot of people I read every day--just scroll down the list at right, all of them are worth reading. The amount of talent and inspiration that these events have unleashed via blogs is amazing. Ok, I have to pick someone at random here (eenie meenie....)

For a second New Orleans Blogger, I'll pick...Traveling Mermaid. I read this blog not just because she writes about New Orleans, but because the blogger reminds me of several friends of mine (even though she and I have never met; see her last post for thoughts on cyber-friends). When I need to escape from the Ugly Truth as brought to me by a lot of my fellow bloggers, I often find a some solace in her posts. And even though I usually hate embedded music loops, her's is cool.

If you are blogging about New Orleans (or about something else, but read a lot of blogs about New Orleans for whatever reason), I hope you'll visit the Think New Orleans blog and consider participating in this particular experiment.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana levee flooding

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Failure Was The Only Option

The story headlined Army Corps if Faulted on New Orleans Levees reports taht the independent study contradicts the Corps' internal investigation claiming the failures were unforseeable.

The civil engineers group also rejected the explanation given by the Corps thatThose who have suggested my last post was too harsh will find it hard to convince me me to that we must go hat in hand, and ask massa nicely for some help. The failure of the Corps' flood protection was as predictable as the storm that would come and bring it about.

the system had failed because Katrina had unleashed "unforeseeable" physical

forces that weakened the flood walls. In a letter to Lt. Gen. Carl A. Strock,

the Corps' commander, the civil engineers cited three previous Corps studies

that predicted precisely the chain of events that caused the city's 17th Street

Canal flood wall to fail

The Corps tries to hide behind soveriegn immunity and their own studies, but it is clear that those charged to protect us failed us, with clear foreknowledge of their implications of their actions. Their only excuse are bits of paper that hold them harmless, paper as flimsy as I-walls they built atop the 17th Street Canal.

The victims of the flood are owed full compensation, should demand it and do everything in their power to ensure it is paid. But compensation for losses alone is not enough. The extent of damage we received is directly tied to the channelization and leveeing of the river, and coastal oil-and-gas exploration. If these activities are to continue, then the nation must bear the cost, and that means funding the necessary coastal restoration and storm protection activities for those of us who have borne the brunt of the cost of these activities.

One important note in this story is being addressed: the danger that will persist from the drainage canals. What is most urgent now is at least being done: the gating of those canals where they enter the lake. This particular improvement was long fought by the the city's Sewerage and Water Board and Jefferson Parish officials. It is now clear that this work must be complete by June 1, even with the threat of rain flooding on low lying areas of the city.

This is critical because, as the engineering study warns, "every single foot of the I-walls is suspect," said Ivor van Heerden, leader of a Louisiana-appointed team of engineers. "When asked, we have constantly urged anyone returning to New Orleans to exercise caution, because the system now in place could fail in a Category 2 storm. It has already failed during a fast-moving Category 3 storm that missed New Orleans by 30 miles."

The gates must be ready by June 1.

The current cry is for Category Five levees. It's a laudable long-term goal, but there are things we need right much sooner. Beyond the gating of the canals, what is needed most in the short term (before, say, the June 1 2007 season) is the relocation of the pumping stations to the mouths of the canals.

When the original pumping stations were build, each was pretty much at the back of town already, and the consequences of flooding over the canals was not significant to the city. Now that the city has filled in the land between the 17th Street and Orleans and London Avenue Canals, the pumping stations must be moved so that we can have capable lakefront levees, and the ability to pump out rain water even during storm conditions.

We can argue about how best to protect the city. Clearly we need a massive program of coastal restorations, and the best levees and flood walls and pumping stations modern engineering is capable of. It will be an expensive and challenging undertaking. The United States remains a wealthy and powerful nation. It is within our capability.

The title of this post was taken from the film Apollo 13, the failed mission to the moon in which engineer struggled valiantly to bring home the three astronauts. The mission director in the movie (but not in reality) tells his team that "failure is not an option". The threat is not just to the lives of three men who clear-eyed and willingly went in harms way, but the prestige of the United States of America

If this nation fails to bring New Orleans to recovery, and to embark on the program of coastal restoration and storm protection needed, it will be the greatest failure in the national history, perhaps the failure that marks the end of the American era. If the nation is no longer capable of this (not just economically or technically, but because we have become so soft and selfish that the nation will not), then the days of American greatness will be behind us.

I keep trying to convince myself in these pages that we have not slipped past that point, that the people I helped to load relief trucks every night for a week in Fargo, N.D.--just as was done all across the country--will demand of their representatives that the right thing be done, and the cost be damned. It was the response to 9-11, and should be the same response here.

If it is not, then we will know that America has fallen so deeply into self-absorption and greed that only a credible threat, one that directly bears on each and every Ameircan, will move the nation to act. Fear and greed drove the response to 9-11, no matter what the flag-waving uber patriots will try to tell you.

As I suggested in my last post, we should give the Ladies of the Storm and Levees.org one last chance to place our case before the government and the nation, before we begin to explore means to compel them, to do what is in our power to demonstrate what the loss of the port and the oil and gas will mean to them, to use fear and greed just as our highest leaders do to place and keep themselves in power.

If our government will not do what is right and just, if our leaders will not prove themselves as the gentleman and ladies they pretend to be when addressing each other on the floor of the House and Senate, if the people they represent will not demand they do what is right and just, then we must look to every means at our disposal to compel them to do so.

N.B.--Republished this after correcting some typos, etc. that resulted posting this from a fuzzy laptop in the wee hours of the morning while exhausted and angry.

New Orleans Katrina Hurricane Katrina FEMA levee flood Bush Louisiana Ninth Ward NOLA

Corps of Engineers negligence

Friday, March 24, 2006

Rules? In a knife fight?

Blogger Ashley raised the idea that New Orleans and Louisiana will have to rely on their own resources in this piece a few weeks back, under the Gaelic name Sinn Fein. Recent developments in Washington reinforce this idea: we are on our own, and must rely on Only Ourselves.

That doesn't mean that full compensation for the negligence of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Category Five levees and coastal restoration are beyond our reach. It just means that we need rely on ourselves, to use our own resources to make it happen. Lets begin by defining our resources.

Oil and gas. The port. Those are the keys. Both are inextricably tied to the collapse of the coast, and both were deliberate acts by the government, made for the benefit of the whole nation at our expense. It's time for the nation to pay the full cost of navigation and flood protection on the Mississippi and for the destruction of our protective wetlands by these activities.

We can ask nicely one last time and explain: the channelization and leveeing of the Mississippi and tributaries is what made the prosperity of the American heartland possible in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Oil and gas continued that prosperity in the 21st century. The bill is now due for the costs of these actions. To save the city--and by extension the port and the coastal oil and gas infrastructure--tens of billions of dollars are needed. All we ask is the same deal people like Alaska get--50% of offshore federal revenue, to pay for it

This is a perfectly reasonable and rational request. I expect them to slam the door in our face.

Fine. If they won't act reasonably, then its time to look at what we can do to shut down the port and oil-and-gas exploitation along the coast, until such time as reason once again prevails.

Everyone agrees that the governor's decision to try to block the next offshore oil lease may have helped focus the dear leader's mind on the issue, since the presence or absence of oil seems to play such a large role in their foreign policy deliberations. And let's face it, as his "people down there" comments of his last visit points out, we are in the view of the central government a foreign place.

Let's not stop at blocking future offshore oil leases. I think we must demand that our typically bought-and-paid-for Congressional delegation stand up to the oil companies and tell them their usually reliable votes for things like off shore exploitation of the gulf off Florida and ANWAR are off the table until we get 100% compensation, Cat 5 levees, and coastal restoration.

No Gulf of Mexico drilling. No ANWAR. No nothing. In fact, I think a windfall profits tax on oil would be a splendid way to pay for coastal restoration, since the oil companies have profited so handsomely from the rape of the Louisiana coast. Don't you Mary? (Hint: if you want to be re-elected, do this. Otherwise, maybe you can run for Hillary's seat when she runs for president).

I think the state also has an obligation to look very closely at the safety and environmental soundness of every inch of pipe and every Christmas tree and pumping station along the coast. Those are are not up to snuff should be shut down. There's a name for this in union disputes. It's called working to the rule. Lets look at the rules we have, see if we need more, and start enforcing them relentlessly.

No money, no oil. Capiche, George?

But why stop there?

River pilotage fees are set by the state of Louisiana. Six thousand ships a year land at the Port of New Orleans and the Port of South Louisiana (above the city to Baton Rouge). I think it's time to re-evaluate those fees. I'm thinking, say, $1 million per vessel sounds about right. That could net us $6 billion a year, enough for Cat 5 levees all through the state, substantial coastal restoration, and full and just compensation for our losses from the criminal negligence of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Of course, I don't think anyone would pay those fees. Ships would try to divert elsewhere. And there would be an immediate rush of Congressional action and federal court rulings to try and stop us. Still, I think we could temporarily shut down the offshore oil port--cutting of 25% of the nation's oil imports--and could push oil to $100. Which would be a good thing for Louisiana's economy.

The real impact would be to the heartland's economy. There simply isn't enough rail capacity to carry all of the agricultural and other bulk exports to other ports. Hell, there are never enough rail cars to go around right now. And even in normal times the cost of rail over barge transport is almost five times as much. People will say "but you'll ruin the port". The simple fact is bulk trade (the kind of business we do in the lower Mississippi) has no other place to go. I think we could cause a significant panic that would make it clear to the heartland what the loss of the port would mean.

I say we give Levees.org and Women of of the Storm one last chance to ask nicely, our elected officials one last chance to prove they put Louisiana first, and the government one last chance to respond reasonably and responsibly and give us the same deal inland states have for oil and gas lease revenue, so that we can rebuild.

Then we give them a swift one where they'll feel it.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

The Ugly End of the Cat

First, how are we going to pay for it? I currently reside in North Dakota, where a (at the time) catastrophic flood destroyed 8,600 homes, and did between one and two billion dollars in damage. As a result, the federal government agreed to provide eight miles of enhanced floodwall and dike (levee) protection, at a cost of $393 million

The state of North Dakota and the city have to come up with 50% of that cost.

Louisiana in general and New Orleans in particular are going to require slightly more than eight linear miles of enhanced protection. And that is going to cost slightly more than $393 million. I think if you add a couple of zeros to that, changing the M in hundreds of millions to a B for tens of billions, you get a little closer.

Where is that money coming from? Currently, state tax collections are off by a billion dollars in 2005, due to the storms and The Flood. On top of that FEMA, is demanding $2.8 billion in reimbursement for their excellent services to date since September. At the city level, New Orleans is considering revoking the tax exemption for non-profits to try to get the garbage picked up. We simply don't have that kind of money

Estimates of building a Category Five system remain speculative, but I haven't seen a figure of less than $30 Billion. Up to half of that would have to be paid by the state and local government. Unless we find a couple dozen of extra billion in cash lying around, Category Five could just be the final nail in our fiscal coffin.

And consider this: only three Category Five storms have every made landfall on the continental United States since we started measuring the weather. Three. Something to consider before we sign up for our half of that 30 Billion dollars.

Next, what good will it do to build Cat Five levees if we don't have Cat Five roofs? As Tim of Tim's Nameless Blog pointed out here, having Cat Five levees could leave us with a bone-dry pile of rubble. The experience of Floridians in the windiest of storms bears this out.

I know among the first things I will do when I get home in June will be to crawl in the attic, and start thinking about how hard it will be to tie my roof down so it stays put up until the point at which the house departs for Munchkin land. (How well, it occurs to me to ask, is my house attached to its piers? I don't know. I think I need an architect or an engineer to figure this out. Kinch?)

Homeowners are going to need assistance not just to rebuild and possibly elevate their homes; they're going to need assistance to make them more wind proof against the day the Big One comes.

Last, how high would those levees need to be if they faced the open Gulf of Mexico? As longtime Picayune outdoors writer and editor Bob Marshall points out here, saving the wetlands is another problem for which bumper sticker solutions just won't do.

Back when I was writing regularly about this subject, I came across a quote by noted coastal authority Sherwood Gagliano, which was roughly this: restoring the coastal wetlands will be as expensive an initiative as the Interstate Highway System or the Apollo space program.

I no longer have the clipping or the notes (quick, where are your notes from 1984?), but it wouldn't matter if Gagliano said it, or someone else said it, or if I mixed up the Apollo and Gemini missions. The fact is, it's an apt way of looking at it. It's going to cost a whole bunch of money, probably as much (adjusted for inflation) as it cost us to send men to the moon. And throw in Skylab for good measure.

While our current resident of 1600 Penn Ave has indicated he'd like to be the President who leads us back to the moon (and as much as people in NOLA would wish him a bon voyage, if he takes Chertoff and Brownie with him), its not clear that America is a nation capable of great works like this.

This is not the generation that built the Hoover Dam, liberated Europe, laid out the Interstates or sent men to the moon. We're the people who brought you the draft deferment, disco and the leveraged buyout, that wants it's tax cut and it's prescription drug benefit. We don't understand sacrifice, because we've never had to face a challenge as large as this.

People in New Orleans are learning about challenge and sacrifice in a way not seen since the Civil War or the Great Depression. To paraphrase a recent political sentiment: 8-29 changed everything. And the guys in Washington just don't get it.

It's clear nobody in Washington is willing to pony up the sort of dollars required to fund just compensation for the Corp's negligence or to pay for Cat Five levees and coastal restoration. They've got the port running, and are getting the oil and gas back on line.

Politically they don't like us, and economically they think don't think they need us. They are simply trying to figure out how to get out of any further obligation as easily and with as little embarrassment as possible, as if we were some pesky sexual harassment lawsuit.

So, how do we change their minds?

Reading a story in the T-P about ten days ago on the lack of compensation for landlords, someone in Baton Rouge suggested those landlords would have to "be incented" to rebuild. That's the (ugly, hackneyed) phrase I was looking for: incented. It doesn't matter if we get Cat Five or Four, or just Cat Three levees that work. The real issue is, how do we open the spigot and get the cash flowing to begin to do what needs to be done?

What sorts of incentives do people best respond to? Greed. Fear. Both of these two work pretty well. They are in fact the keys to power, if we take our current leadership as our example. I think we're going to need to look at how to leverage these two great motivators to remind everyone in that part of the world to our north that New Orleans and the Gulf Coast are important to them, that it will cost them a lot to lose us.

I'll save most of my thoughts on how to do that for a follow up post. Let's just say that the Governor's idea of holding up the offshore oil leases is a timid but good start. That got their attention. Now that we have our attention, I think we need to ask them about the rules in a knife fight.

N.B.--To find out how you can help make these things happen (without waiting for my next post, or having to kick anyone below the belt) please visit www.levees.org and volunteer to help.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers Category Five

Sunday, March 19, 2006

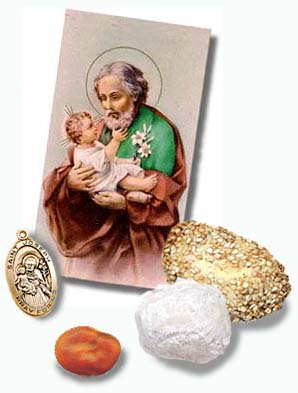

Virtual St. Joseph's Altar

With so many still not home, there are probably altars not being offered this year all over the city. But many are back, including one in devastated St. Bernard Parish and the big one at St. Joseph's on Tulane Avenue. Searching for pictures, I found a tiny thumbnail of one of an altar at Brocato's, one of the altars that will not be there this year.

For those unfamiliar with the custom, there is an explanation on the virtual altar site, including explanations for the various gifts of food offered and their symbolism.

With the city's large Italian population, St. Joseph has always been one of area's most important saints. When I would bring my wife or family home to visit, I would often point out how the feet on the statues of St. Joseph would be worn, as men would often come to pray to him, laying one hand on the saint's feet as they did so. I don't know if this particular form of devotion is universal, but I've noticed the wear on most of the older statues I've seen in NOLA

I hope to convince my wife to go out and visit the altars today, even though she will probably want to stay in and paint the living room of the new house. While St. Joseph is considered "officially" the patron of the dying, fathers and carpenters, he is also widely regarded as a patron of families, in his aspect as patron of fathers.

As I posted somewhere else in a discussion last night, a woman who would leave her children and old home behind and move into a strange house in an alien city, all for love of her husband, is in need of intentions to and attention from St. Joseph. So, as the father of this temporarily severed family, I ask: may he protect and cherish and nourish our separated family and our new house.

And keep an eye on that carpenter cutting the new door and working on the kitchen.

Oh, and please calm the new home buyers who have a contract on the Fargo house, so that we may all get moved and reunited in NOLA on time.

So, enjoy St. Joseph's day, and if you're far from New Orleans today, don't' forget to visit the virtual altar.

Don't leave without your bag.

Saint Joseph St. Joseph Altar Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana levee flooding

Friday, March 17, 2006

If I Should Fall from Grace with God

If I'm buried 'neath the sod

And the angels won't receive me

Let me go down

Let me go down

Let me go down in the mud

Where the rivers all run dry

- Shane McGowan of the Pogues

On a day when many New Orleanian's thoughts turn to Parasol's and the pubs scattered across town, my mind wanders over to the great monument to the Irish in New Orleans, the New Basin Canal, which ran from about where Union Station stands today to Lake Pontchartrain.

Most of it's gone. All that remains are the right of way of the Pontchartrain Expressway, the great neutral ground between West End and Pontchartrain Boulevards, and the small basin that runs the last half mile or so to the lake.

If you say Irish cemetery to someone from New Orleans, they'll think of St. Patrick's on City Park. The great burial ground of the Irish is the New Basin Canal route itself, where the remains of somewhere between 8,000 and 20,000 Irish laborers lie buried in the spoil banks, near where they fell. Stand anywhere along the route of the expressway, and you stand on the bones of the Irish, people hired at a dollar a day to dig the canal so that the wealthy of New Orleans need not risk their slaves in the dangerous work.

Today, all that stands in remembrance of the Irish who built the canal is a Celtic cross in Lakeview near West End Boulevard and Downs Street. I didn't even think to check on it when I drove around Lakeview when I was home Mardi Gras week. It's fitting there should be some remembrance, in a city famous for its cemeteries, for the jazz funerals, for the way we have come to very public terms with death.

That the cross stands in Lakeview is a fitting reminder that The Flood was not the city's first experience with mass death or with disaster. Our entire city is a monument to death and disater overcome. The area of cemeteries where St. Patrick's and all the other cities of the dead stand was once the back of town, where the remains of the yellow fever victims were kept away from the living.

The great fire of 1788 that ravaged the old French city left the French Quarter a monument to Spanish architecture. In Christopher Hallowel's book Holding Back the Sea is a plate of a lithograph of nineteenth century flooding in the downtown area reminiscent of recent news photos.

New Orleans sprang back from these previous disasters, just as Chicago rebounded from its great fire, and San Francisco from the famous earthquake. Still, some commentators wonder if New Orleans can recover once again. They point out that in other citywide and famous disasters of the past, the damaged cities were on the rise, not yet at the peak of their potential.

New Orleans before the levees failed, they argue, was a city past its prime--shrinking in population, losing company headquarters, mired in poverty and crime. They suggest that New Orleans is a city that has been passed by history, and that this will make a difference in with city's ability to rebound.

Perhaps we have been bypassed by history. But history is written in mud by the marching boots of armies, scrawled in slag left by the great engines of industry that tear nations apart, remake them in ways their people do not understand.

Perhaps it is a good thing to be left behind by history, a place at the margins, inconsequential to those who measure the world in divisions of troops and the splitting of stocks. If we are of no consequence to the legions of fanatical Christian and Islamic warriors who would destroy the world lest if fall into the wrong hands then maybe, just maybe we have a chance to save ourselves.

The Irish are no longer at the center of history. The great moment of the Irish people is chronicled in the book How the Irish Saved Civilization, which argues the Irish preserved learning and culture through the Dark Ages, then sent out legions of monks to restore that heritage to Europe. That golden moment was a millennium ago.

Today's Ireland, while not a nation at the center of events, is a thriving place sometime referred to as the Celtic Tiger. It's economy is one of the fastest growing in Europe, with a robust high tech and medical sector, as well as strong legal, accountancy, finance and call center industries.

This Celtic Tiger is not like it's Asian or American counterparts. It is not a place of glass skyscrapers and souless modernism. People live in the old houses, and follow the old ways. They did not have to give up the leisurely lifestyle perfected over generations to achieve prosperity, or remake their landscape in the image of Dallas.

Most Louisianians would feel immediately at home in Ireland, as I did when I visited over a decade ago. The joie de vivre of music, food and drink are so like those of Louisiana, it's as if you discovered a new parish, a lost part of Acadiana. Fiona Ritchie, host of the Celtic music show Thistle & Shamrock, once endorsed my own personal view--the Acadians are the lost tribe of the Celtic race. After a day in Ireland, you would understand why.

I think we can learn a lesson from the Irish, should study their ways as we are studying the dikes of the Dutch.

To prosper, we don't need to give up the life that makes New Orleans and Louisiana the place we all love, the place we all insist we will come home to, the place that must live again. Prosperity is possible in a town where most of the buildings are generations if not centuries old, where a pint at lunch is as common as coffee in Kansas, where people live for the craic, a Gaelic word best understood as what happens in a Irish pub when the good times roll.

I think it's possible to be bypassed by history, and to prosper in spite of that. I think success--which for us is not just rebuilding, but rebuilding better--are possible without giving up what we love about this place. We have only to look to the Irish for an example.

So, as we celebrate the unique American holiday of St. Patrick's Day, let me lift a glass to the forgotten thousands of the New Basin Canal, and to their cousins who never left the old country. You made this city what is is, and can teach us what it can become. You show us that we can embrace and celebrate our past and ourselves while we make a new future. And that there's no need for the music or the drink to stop to make it happen.

"This land was always ours

Was the proud land of our fathers

It belongs to us and them

Not to any of the others

Let them go, boys

Let them go, boys

Let them go down in the mud

Where the rivers all run dry"

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers Saint Parish St. Patrick's Day Ireland Irish

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Levees.org Update

Dear Members,

In 10 days, we will unveil our next strategy to focus even greater attention on the US Army Corps of Engineers' central role in the metro New Orleans flood. Meanwhile, we must get our ducks in a row.

Only the power of the citizens powers us, so we rely on our volunteers. I am proud that our ranks have grown to 1300 members; but there is much to manage!

Please choose an area of interest from the list below and email me with your choice:

1) Sign committee

2) Research committee

3) Neighborhood rep (be a liaison in your section of town!)

4) Leaflets committee (flyers and pamphlets)

5) Bumper sticker committee

6) Membership committee (find new members)

Can't decide? Email me and say "I'll help on a committee that needs me." Again your response to this email is a signal that you want to help, not a commitment.

Thank you!

Sandy Rosenthal

Founder

www.levees.org

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

The Tree Shaded Avenues

The park, and it's canopy of trees, is an indelible stamp on my soul. I think I was more devestated by the view from my mother's place at Park Esplande, or my drives down City Park and Wisner than I was by seeing Lakeview. Homes can be rebuilt. Stuff can be replaced. Many of those over 1,000 lost trees will take a generation or more to replace.

I almost cried when I saw the magnolias leafed out and happy looking at the entry to the Park at Lekong Drive (the road the NOMA, if you're not a park-head). Many of the trees, like the city, will survive. Bringing back the urban forests of New Orleans will, like rebuilding much of the city, be the work of lifetimes.

New Orleans is habitable, in spite of the sub-tropic swelter, by the grace of its trees. All of the best places are cooled by the filtering of the unrelenting sun through the canopy that overhangs the main avenues, all the best spots in to stop and sit, and any house worth living in.

Step out of the airport and into your limo or taxi, then wander for a week between your downtown hotel and every notable spot in the French Quarter, and you may never see a notable oak or other tree. I’ve walked through or around Jackson Square countless times, and can’t recall a single exceptional specimen.

The closest most tourists get to touching this urban forest is riding the streetcar to Audubon Park and back. They fan themselves furiously with a street map and complain that the cars aren't air-conditioned, they gawk at the houses and squeal should they see the Roman Candy man stopped at a corner. The trees are such an integral part of the scene they are lost among the mansions.

The true tourists, those who line up on the shadeless pavement outside their hotels to fill the Greyline buses, will certainly make it to City Park, and see the Dueling and the Suicide, the 600-year-old McDonough, all the ancient live oaks preserved there. They ride along Dreyfous and City Park Avenues and marvel at the stands of grandfather trees bearded with moss, whose branches descend to the ground as if reaching down to steady themselves. They see the cypress that populates the margins and islands of the lagoons, the knees like the accidentally exposed bones of something long buried, the frightful specimen on the small island where Wisner meets Carrolton and City Park, its twisted branches haunting in winter.

When the visitor abandons the bus and ventures on foot along the lagoon, or steps down from the streetcar and walks down St. Charles, only then do the trees become a central element in the picture: the stout trunks and wandering roots erupting through the upended pavement in a violent attempt to reclaim the city for the forest primeval, the great canopy of branches that filters the light into a wavering and indirect illumination akin to candlelight, the ideal illumination for Faulkner’s aging courtesan.

If they are uptown, they might see the flowering rows of crepe myrtles that line the boulevard between sidewalk and street. Were they to tour the lakefront, they might see the stand of evergreens just north of the levee we called Pinecone Forest when I played or idled beneath them as a child. In almost any neighborhood, they would find the towering trees that mark a mature city, one where generations have passed since saplings were planted on newly platted lots.

If this same visitor steps out of their vehicle today (Ed. note: this was written in I believe October 2005), they will see this: great piles of broken wood heaped in the sun, naked and shattered branches traced against the unrelieved blue of the sky. Everywhere, the canopy is torn away, limbs broken, trunks reduced to tall stumps. Many trees survived, but many more were lost, leaving the streets exposed to the unrelenting sun and the driving rain.

Esplanade is one of these denuded avenues, it’s great trees broken and battered by Katrina. The painter Degas lived here once, and it is easy to imagine he would choose a house where there is infinite variation and change in the light, where the world is already softened in a way that the painters of the late nineteenth century understood. Today, the historic plaque that marks his nineteenth century home in the city would stand exposed to the sun all hours of the day.

The great historic avenues of oak—St. Charles, Esplanade—suffered, but these trees will come back. All the great oaks have surrendered branches and leaves to past storms, and come back. In a place where hurricanes and powerful subtropical thunderstorms are as regular as Carnival, these trees have grown to heroic proportions only because they are well adapted to the place.

So, too, the flexible cypress around the lagoons of City Park, naturally suited to sit in the water and bend before the wind. The modest neighborhoods trees faired poorly. Many lots in the older residential sections are too small for the great oaks. Smaller trees—water oaks, pecans, loquats, sweet olive—were more common. In the sandy fill of the reclaimed lakefront, pines were as frequent as lamp and telephone posts.

One of my clearest memories of Hurricane Betsy thirty years ago is of a large oak upended by the storm. It’s root ball seemed as large as a car. The tree was largely intact; it’s thick branches themselves stronger than the great wind. And that was its undoing. Before I left the city, I could easily recall the hurricanes of my childhood by walking past a tree’s truncated branch, and remember the name of the storm or the school grade I was in when it came crashing down.

The floodwaters killed all of the low vegetation. The St. Augustine grass is all brown, the azaleas are all dead. These things, however, are easily replanted. A lawn can be brought back in a year. New shrubbery can be back before its time to trade the car. Trees, especially the great trees of a city centuries old, are not quickly replaced. They are planted not for the next season, but for the next generation.

The once reliable shade made outdoors just bearable on all but the worst days. It was an essential element in a city where mail carriers wear pith helmets to survive in the sun. Now those porches and patios, barbecues and swings will sit in the sun, the metal parts untouchable in summer. In the older neighborhoods, where every house was built right up to the sidewalk, sitting on a shaded stoop will no longer a sociable way to deal with the heat.

More likely, people will retreat back into the air conditioning or the unnatural, fan-blown shade of a darkened indoors, will no longer stroll in the late afternoon or early evening through their urban forest. Instead, they will begin to live like the residents of some desert city of the southwest, where sidewalks are superfluous and pedestrians as rare as open water.

The trees will not be all that is lost.

Cross posted from Flood Street.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers trees urban forest

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Elsewhere in the news

Fargo, I mean. Oh, you thought I meant that other city perched at the edge of the continent &c. No, I wasn't talking about New Orleans. I was talking about Fargo. I'm moving back to NOLA in June, and my wife is already there. But for now, I remain where I've been for over a decade, in (or around) Fargo.

Yes, the city in the movie. Or at least in the name of the movie. The movie was actually shot in rural Minnesota, and not in North Dakota. I spent about a half year working for a politician in northwest Minnesota (one of two bachelor-pilot-musicians in Congress I worked for, and what're the odds of that?). When I worked for the congressman I saw so many places like the town where the erstwhile female police officer questioned people; little, half block long cul de sac streets off a highway, huddling around a water tower like serfs living under the keep.

Yeah, I know those places, all near a wooded lake where in December you can drive an F-350 dragging a ice house the size of a FEMA trailer behind you onto the lake, where you can always borrow a neighbor's chipper/shredder when you need one. That Minnesota. Lake Woebegon. You know the place.

North Dakota only has a cameo on screen, the scenes where the guy is looking for the money hidden on the side of the road. That one shot, of the fence line in the blowing snow, that's North Dakota. At least, that's North Dakota in January or February. In early March, eventhing finally begins to thaw-at least, part of the time--until the city is one fantastic ice sculpture of tire track pressure ridges, on which we walk and drive for entertainment.

A few people up here still ask me about my mom and all. Well, they don't use those words, but they ask how they're doing. The few that know my wife is already in New Orleans wonder how she's doing as well. But they don't ask about New Orleans, about why we're moving there, about why we'd want to.

Like the rest of the nation, Fargo has Katrina fatigue. There's just so much of someone else's disaster a person can take, before they turn away. It might be different if I lived in Grand Forks, which experienced its own disastrous flood in 1997, ranked the eight worst natural disaster in U.S. history. (Read this interesting blog post from someone with ties to both the Gulf Coast and the Red River Floods, if you don't remember the 1997 floods in the Red River of the North).

It's so easy for people in this part of the world to just turn away after six months. People in New Orleans seem so needy, so demanding. There was a major ice storm late in the fall, and an email began circulating claiming how much better North Dakotans were than those people in that part of the world.

As the Snopes article points out, North Dakota didn't hesitate to belly up to the federal trough and demand aid, as they've done every single year for the last decade. North Dakota is tied with Louisiana, Texas and Ohio for ninth place among states with the most major disaster declarations by the central government.

In fact, North Dakota has the longest streak of consecutive major disaster declarations of any state in the Union. With a state population slightly smaller than that of antediluvian Orleans Parish, the state has received $711 million in federal disaster assistance in the last decade. That doesn't even count money for agriculture, which comes separately.

From 1995 to 2003, NoDak received another $796 million in crop disaster assistance, coming in second behind Texas in the total received, according to this story in the Des Moines IA Register. Interestingly, only about 58% of farmers nationally avail themselves of federally-subsidized crop insurance, but they expect (and receive) regular government disaster aid.

Yes, a nice chuck of that $711 million was tied to the 1997 flood, which damanged some 8,600 homes and was tagged as causing between $1 and $2 billion in damage. Without that particular event, N.D. would drop out of the top ten, most likely. But the fact is, there's a lot of equally needy places getting aid year in and year out. Unlike New Orleans, they weren't even the victims of the gross negligence of their government. They all just choose to live in places where life's a bit dicey. Just like NOLA.

I think it's fair to ask the people in North Dakota, and any of the other states on the top 10 list of federal disaster aid: if you accept the idea of short-changing New Orleans, how do you know you're not next? (If you don't think the city is being short-changed, start by reading this earlier post, and then some of Da Po' Blog's excellent deconstruction of the actual amount of federal aid, as opposed to money owed for flood insurance premiums paid, thats going to the city. )

People in all these disaster-prone states live in a high risk environment, and require a steady stream of federal assistance to do so. I'm writing about North Dakota because it is the state on that list (excluding Louisiana) that I'm familiar with. Chronic droughts west and flood east, blizzards and ice storms, tornados and derechoes: it's like a disaster buffet at the Sons of Norway. Still, there are even more chronic complainers in other states.

People in all the states that top the list of leading disaster assistance recipients need to start asking themselves: what will you say when others question whether people really should be living there? Why should the rest of the country subsidize your foolish choice of locations?

If you let the government walk away from New Orleans, how do you know you won't be the next ones crossed off the list?

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers North Dakota Fargo

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Structure 117

... the three-bedroom house where Herbert and Mary Warren raised eight children at 2330 Roffignac St. in the Lower 9th Ward…lay on Winthrop Street, a block and a half from its original site -- yanked off its foundation and sent spinning through the neighborhood by a wall of water loosed by the collapse of the Industrial Canal levee almost a mile away.

Broken and swaybacked, its squared corners and vertical lines smashed into crazy angles, Structure 117 sat in a vast landscape of similarly wrecked and abandoned houses, remarkable in only one way:

It came to rest in the street.

Reduced to a ruin by the failure of the federal levees, Structure 117 will live only in the memory of the families that called it home. It is easy to imagine what they will remember of it, even if the rest of us are instructed to call it by the number on the final mark it bears, the scar of a red demolition sticker, even if we have only a vague picture of the shattered frame of a wooden bungalow falling beneath the yellow claw of recovery.

I have not seen Structure 117. When I was home, I visited Lakeview, but I could not find time to go to the Ninth Ward or to St. Bernard Parish. I crossed the Ninth every day when I worked in Chalmette, but I did not have the time, or the strength to go to those places. Seeing Lakeview, the neighborhood to which I was carried home from Hotel Dieu and which I visited almost every day of my life for 30 years, was enough, was as much as I could bear.

Still, it is not hard to imagine Structure 117. It looks in the newspaper pictures to be a post-war frame bungalow much like those that filled Lakeview before such houses became teardowns for the wealthy. Both Lakeview and the Ninth Ward were mid-twentieth century suburbs, one built for whites and one built for blacks.

Structure 117 contained, we can be sure, a kitchen. In it, I can clearly see a small porcelain over steel gas stove. Sitting atop the back panel there was almost certainly a big box of Diamond matches, and a bottle of Tabasco or Crystal ready to hand. Once pots of gumbo as dark as chocolate or as light as café au lait simmered there. On Monday, red beans filled the house with an aroma of earth and leaves and meat as old as the places men first walked the earth.

The rooms and hallways of Structure 117 would be familiar: an L-shaped living and dining room in the front, with a hallway down the middle. Down that hall was room for that essential washer and dryer, and perhaps one-and-a-half baths, no waiting and no walkthroughs. The rooms were not much larger than those of the shotguns and cottages Structure 117 replaced, but they were perhaps a bit darker and closer, needing lots of outlets for the electric lights that would fill them with light and sound and make them livable, and for the window air conditioners that would transform the life of the South, making a porch superfluous.

The layout was not much changed by the time Marrero began to rise out of the swamps of the West Bank, where I once joined my girlfriend’s working class cousins for Thanksgiving dinner and learned to eat baked spaghetti and cheese with my turkey. Structure 117 was of the same vintage, a recent addition to the plan built in 1962. It was, like Structure 116 and 118, the place an entire generation lived, the place they all saw on their new televisions. And the lives that played out within those walls were much the same, Ninth Ward or Lakeview or West Bank.

Structure 117 and all its fellows were built on poured slabs right on grade, like all the homes of that era. Why would you want to build on piers, with rats and feral cats nesting under your house, with pipes that will burst in the first hard freeze, with the cold and the draft of the old way? It was the post-war era, and time to put aside the old ways. It was the time when the engineers and accountants and ad men conspired to turn Huey Long’s stump speeches into a solid business plan, to build every king a castle he could afford.

They built Structure 117 and all its like according to the best modern American way, as regular as Model As in the fashion perfected by Ford and proven by the war, according to the best laid plans of the men who built not just the Structure 117 and the new neighborhoods that held it, but the cars and the interstate highways that joined them, who built the ICBMs and the bombers to keep it safe, who built the levees and the floodwalls that protected them.

In time, all of those failed Structure 117, and the people who called it home. The highways slashed through the old established neighborhoods where Structure 117s residents grew up as ruthlessly as Patton’s Third Army, and the exhaust of all the cars darkened the sky and poisoned the air and water and ground. The ICBMs and the bombers protected us from our enemies, but not from ourselves, not from the people Ike warned us about. And the levees failed as well, as predictably as a Greek tragedy, hubris angering the indifferent-at-best gods who sent the waters that overwhelmed them.

The levees and floodwalls failed to protect Structure 117 not because they didn’t now how to build them, but because they placed the accountants and the ad men up on the same exalted peristyle as the engineers, because they wanted to believe the lies in their business plans and advertising campaigns, because this was the generation that would build the tower to heaven.

It is the same sort of efficient planning that built Structure 117 that reduced it from a home to a numbered line at the top of a list on a clipboard. To the man with the clipboard directing the fellow atop the backhoe, does it still matter that this was once a set of bedrooms where lovers spooned and wept, of bathrooms where men shaved and women bled, of yards where children played and gardens grew, of kitchens where pies cooled and chicken fried in great black skillets?

The owners came to watch the end of Structure 117. The newspaper tells us this:

It doesn’t tell us if he wept the first time he heard from his grandson the NOPD officer of Structure 117’s ruinous journey from its slab and down the block and into the street, or what he felt when he was first allowed to see Structure 117, and could not enter it to save a single thing.Herbert Warren was there for a while to see the end of his home. He said he had visited earlier, but was unable to retrieve anything from inside. Mary Warren was unable even to enter the house.

"She suffers from the asthma, so she couldn't," he said.

Who weeps for numbers? Not the men who built these neighborhoods, or their grandsons who plan the demolition. A longshoreman who rebuilt Structure 117 himself after Betsy flooded it in 1965 just three years after he bought it, Herbert Warren is not likely a man who weeps in public.

If no one weeps for Structure 117, we will have forgotten what the Greeks knew thousands of years ago, about hubris, about catharsis, about the human condition. We will not learn the lesson those authors sought to teach their audience. Instead we will rear Structure 117 Mark II behind levees not much changed from those that failed, with predictable results.

It won't matter to Herbert Warren. As he watched the end of Structure 117, he told the newspaper he would hoped to stay in the city, but not be back to the neighborhood. Two floods, he says, are all he can stand.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers Ninth Ward demolition Lakeview Structure 117

Monday, March 06, 2006

Home

Ok, that's not entirely true. My wife Rebecca said "dork" as she took this.

NOLA New Orleans Toulouse Street Louisiana levee flooding

OM Sri Ganeshaya Namah. Thanks to St. Jude for Favors granted. And to Maitri and friend for the rice krispy bars and other assistance. See y'all at Samadi Gras.

Sunday, March 05, 2006

The River

I grew up as far from the river as one can get and still be in the city, in a lakefront reclaimed from the lake’s shore in living memory. For me the Lake and Bayou St. John and the great drainage canals were the defining waterways of my youth. These were accessible, and mysterious in small ways.

The old Spanish Fort on the bayou, the antique pedestrian bridge that crossed the Bayou just there, the ribs of a long sunken boat visible just beneath the surface beneath the crumbling brick walls: behind the levees one entered another world. Even the Orleans Canal seemed a bucolic waterway in it’s last stretch before the lake, reached on the east side by crossing a vast park filled with trees and climbing a tall levee, which seemed mountainous to a boy used to an apparent flatness in the world.

In those days before the Moonwalk or the Riverwalk, the river was a distant and mystical presence, often spoken of but rarely glimpsed up close. It hid behind floodwalls and levees; behind the warehouses that lined Tchoupitoulas Street, themselves fortified by ramparts of railroad tracks. The riverside neighborhoods were alien and dangerous, like the Loup Garou, waiting to swallow naughty little boys. The River had at once as much and as little reality as the godhead I was told resided in a tiny wafer of glutinous bread.

The immensity of the River was inflated when revealed from the heights of the bridges that spanned it, the Huey P. Long and the Greater New Orleans Bridge. It was, to a small boy, like a snapshot of a pre-Cambrian world; from something so huge and remote, one expected great monsters to suddenly break the surface, and swallow the toy ships.

When I was much older I remember riding the Canal Street Ferry to Algiers with my father, to walk the streets he knew as a child new to New Orleans. His family came up from Thibodaux in the early 1930s, leaving a house where French was the first language, a house on another Canal Street facing a different bayou than the one I knew growing up.

We strolled through the streets and looked for the house of his early boy hood, and he told us of days when they would swim in the river. Swim in it! I had only heard tales of sucking quick sands along the shore, and of whirlpools that would swallow anyone unlucky enough to fall in, taking their bodes down to great depths peopled by mythically giant catfish, never to be see again. And my father swam in those waters.

On that day, the River entered my life as a force, as something to which I had a connection. It lost none of its mythic proportion. Instead, my father was raised up into a figure out of Bullfinch’s or a character from Twain.

My father made the river an indelible part of his history, and mine, in other ways. He had joined the Second Battle of New Orleans, and helped lead the fight to save the River from plans to further sever it from the city by building an expressway betwee the Quarter and the River. He was president of the New Orleans Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. He had challenged the head of the downtown business establishment pushing for the expressway to debate him on citywide television. The publisher of the newspaper had threatened to withhold my older sister’s wedding announcement in retaliation, in words that a hundred years earlier would have ended not on WWL-TV, but beneath the Dueling Oak.

My father became the man I think of when I look at the self portrait that hangs in my office, a figure who moved across and not just through the landscape of the city's and the river's history.

***

When I came to work for the small newspapers in Gretna and St. Bernard, I became a frequent passenger of the ferries. For a time, my only vehicle was a small motorbike, and I came to rely on the ferries almost exclusively. My working days often began and ended standing at the railing of the lower deck, watching the deck crew hand lines as big as my arm, as the pilot let out a blast on his whistle to announce our crossing.

That was when the river really entered my life, when I began to feel myself a citizen of a river city, at the mercy of the currents and the skills of a pilot, planning my day in part by the schedule of the boats, mindful of its floods and the debris that swept past the ferry rail, bound for the sea.

Now, when I take my children back to New Orleans, we inevitably travel to the zoo, and return from Uptown on the riverboat Audubon that travels from the foot of Canal to the Park and back. I point out the bright new container ships and the rusting banana boats, explain the mysteries of the Plimsoll mark, and name the wharves as we pass them like a list of the boats on the shores of Troy.

Now that I hope to come home to stay, I think often of the river. A famous author once wrote of memory and home and a river, and told us that we can’t go home again. The ancient aphorism tells us that we cannot step twice into the same river. I know that they are right. I believe that they are wrong.

The city I return to will not be the city I left. Too much was lost in the flood, swept away by the waters of my childhood, the waters of the lake and the canals I once thought idyllic. But before I had crossed the Parish line twenty years ago, the city in my rear view mirror was not the city I grew up in. Time and commerce had done more to erode the city of my childhood than even the greatest river on the continent could.

I know that when I return, I will go back to the Moonwalk. I will climb the steps that my father helped to build, that are in my mind his great monument, and the river will be there. It will not be the same river he knew and swam in as a boy or fought for as a man; it will not be the river I first saw from high atop the Huey P. Long Bridge or the one I watched from the levee at Riverbend as a youth; it will not even be the river I took my children down just last year.

It will be as much a river of memory, and a river of dreams, as a physical river. But that, in the end, is the river it has always been, from the time of LaSalle and Bienville until today. I will find that river, just where I left it, up and across those steps. I will take my children and climb them, and there I will tell them the story of their grandfather and the river.

And I will be home.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levee flooding Corps of Engineers Mississippi River Mississippi

"And when we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard nor welcome, but when we are silent we are still afraid. So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive." -- Audie Lorde

Any copyrighted material presented here is done so for the purposes of news reporting and comment consistent with USC 17 Chapter 1 Title 107.