Sunday, November 26, 2006

Shut up and be thankful

The demolition of an archtecturally significant building is not our concern. A decision has been made by Our Betters about the future of the city. To oppose it is to oppose progress in reconstruction. If the arguments ring familiar, perhaps it is because we are recapitulating on a smaller stage the contest we all knew would come after the Federal Flood: a restaging of the Third Battle of New Orleans over the Riverfront Expressway.

The choices presented are cartoonishly stark: progress in reconstruction versus obstructionist preservationists who threaten the city's future. Our political elites in the person of council members Cynthia Hedge-Morell (an alumnae), Arnie Fielkow and Oliver Thomas, the influential board and alumni of Holy Cross School, and the Archdiocese take the parts of the city and downtown business interests. The Times-Picayune perfectly recounts the role of mindless booster it played decades ago, although WWL's hosting of a ten minute news segment featuring only proponents of demolition must give pause to former editorialist Phil Johnson who ultimately championed the opposition to the Riverfront Expressway.

Arrayed against them are a handful of preservationists and parishoners of Cabrini, led by a Tulane University architect (and parisoner) who demands we stop and ask: Is this building important? If so, can we have a dialogue about how Holy Cross and the building can coexists? I do not mean to assert that the preservation of a single, modern church is equivalent in importance to preserving the French Quarter and public riverfront access. However, the battle is important because it may define who future battles over more significant buildings or neighborhoods are fought.

The problem is that the pro-demolition faction are set to do battle, not to have a dialogue. Much of the neigborhood is swept up in this approach, having been told that it is an all or nothing decision, one that might triple the value of the storm ravaged properties. There is no need for dialogue with the opponents. Instead, they are to be harrased and crushed. An example of this approach is the neighborhood association and Archdiocese's attempts to drag Tulane University President Scott Cowen into the fray, in an attempt to silence Tulane architecture professor (and parishoner) Steve Verdeber.

Interestingly, the reason that there is an accessible riverfront in the French Quarter and CBD today is because of a quixotic battle against Progress led by a few architects and perservationists, including members of the Tulane University School of Architecture facility. The opponents won that battle and we had a vibrant rebirth of the Poydras and riverfront corridors in spite of the lack of expressway.

The approach of the pro-demolition faction may be driven in part by the key role of the Archiocese and it's hatchet man Fr. William Maestri, a cleric of such profound political sensitivity that the parishoners of St. Pius the X started a petition drive to have him removed when he was assigned as their pastor. He has been in the forefront of decisions by the church to close or merge parishes and schools with no concern about the parishoners or parents and students. Maestri and the church have no concern about neighborhood sensativities, having been appointed by God to make such decisions for us.

An ugly battle over redevelopment was going to come someday, one that turns us one against the other instead of uniting against our real foes: a disinterested Washington political leadership unwilling to pay the deferred cost of a generation of raping the coast for oil, and an insurance industry that will cheerfully close the coast to business. Our entire nation's political culture is increasingly wired to deal only in absolutes, and to refuse dialogue with the other side because, well, they are the "other side". New Orleans in particular has always been split by divisions not just of race but of class and section that make battles of thsi sort almost inevitable.

The battle of Cabrini may seem a small one but it represents the way in which reconstruction may proceed. The Unified New Orleans Plan process is unfolding under the leadership of the Greater New Orleans Foundation. The GNOF's board represents all the expected parties: the old-line law firms and banks, Tulane and Entergy, all of the people I mean when I spoke above of Our Betters. It is a creature of the sort of people who fill out the ranks of the better Carnival krewes.

My own uneasy feeling is that the UNOP process is intended to rein in the freewheelingly democratic alternative unleashed first by Broadmoor and then by the City Council's own planning process. UNOP will take the direction of the recovery out of the hands of the neighborhoods and put it back into the hands of the people who have always run this city. I have seen nothing to disturb this bleak picture, from the secretive appointment without neighborhood input of a Community Support Organization to represent neighborhood interests, through the inability (or unwillingness) of the planners to tell us which parts of recovery citizens will be allowed input into.

The combination of apparent secretiveness and incompetence that characterizes UNOP is a mirror of the way Mayor C. Ray Nagin has run the city since his re-election. Large and critical decisions are made in secret and presented as fait accompli to us, to prevent us from questioning the wisdom of those decisions. Either accept the new waste management contracts, or the garbage will pile up in the streets come New Years.

Our Betters hope to put back into the bottle the democratic genii unleashed by Broadmoore and the neighborhood planning process, and by the upset election of all new faces to the city council from the repopulated neighborhoods . They have Big Plans and are not about the let neighborhood activists or preservationists upset the opportunity for Big Money that will follow the release of federal recovery funds. If necessary, they will turn out angry mobs like that at the recent city council meeting over a city inspector general, or that which formed on the steps of Cabrini Church to support demolition.

The Cabrini battle is important whether or not one finds the church architecturally significant. It is important because Our Betters are playing us so that our energies are spent in bickering with each other instead of having a real dialogue about the future of the city. That's why we need to force the Archdiocese and Holy Cross to the table. Everyone wants the Holy Cross School to remain in New Orleans. All we ask is that decisions like this be made transparently and through dialogue, that everyone have a seat at the table that decides what sort of New Orleans Holy Cross will be a part of, what is to be preserved and what can be let go.

If we can't force the powerful forces of the pro-demolition side to the table on this issue, we are all liable to wake up one morning and realize New Orleans is a city greatly transformed in ways we never saw coming.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK wetlands news rebirth Debrisville Federal Flood 8-29 Rising Tide Remember Cabrini Church historic preservation

Friday, November 17, 2006

Our State: The only insurance we really need

For the first time in a crisis a year old, today's Times Picayune contains a suggestion that the government may need to directly interdece. The insurance industry is predictably unimpressed, but do we really care what they think any longer? The private market has failed us, has become a dark alley down which we are all forced to march to await our turn to be robbed. The private insurance racket is poised to destroy the Gulf Coast in a way no hurricane could.

Unlike the forces of nature, the insurance racketeers are a force against which we can fight back.

Imagine if the auto industry or the oil companies decided they have grown weary of California's endless air pollution regulations, and announced that they would no longer sell cars or pump gas in the state. How long would that state's leaders in Sacramento, or the federal government for that matter, allow that to stand? Not for a minute.

The theory of insurance is simple. A group of people pay money into a pool which is invested and grows, and out of which those who file claims are compenstated. From the remaining funds in the pool, the insurance company takes a modest profit for administering the trust. It is a model that has worked for a millenium and enabled commerce to flourish in a risk world.

But times have changed since the first traders banded together to reduce the risk of medieval sea voyages. The theory of modern insurance is that large corporations take people's money, then attempt in every way possible to avoid paying out any claims thus maximizing profit and mininum cost and risk. In Mississippi it appeares the insurance companies may have engaged in organized criminal conspiracy to deny payments. If forced to pay out, the companies raise rates to collect the cost of claims a second time from policy holders. If anything interfers with this one-way flow of cash into their coffers, they threaten leave the market.

It's time to simply throw all of the bums out of the state, and move everyone into a state pool for all insurance: property, life and casualty, auto, busines continuation: everything. If the national companies will not write property insurance, I see no reason to allow them to continue to profit in other business lines.

We can expand our market pool by refusing to recognize out of state auto policies, for example. Visitors would be able to purchase temporary coverage at the visitors centers in the same fasion people driving into Mexico purchase insurance from Sanborn. Transportation companies would purchase insurance for their Louisiana routes and deliveries in the same fashion that multi-state companies purchase workers compensation insurance, on a state by state basis.

We should work with other coastal states to move in the same direction, so we can create a reinsurance pool for storm damage that covers the entire hurricane coast. When our neighbors get hit, we help them out, and vice versa, with the cost spread out over millions of policy holders.

The state insurance company should set actuarially sound premiums, and purchase sufficent reinsurance agasint catastrophic loss. It probably won't be as cheap as property insurance in the Midwest, but it would likely be cheaper than relying on the current private[er] market. The Social Security and Medicare insurance programs operate on overhead of less than three percent, with no margin of profit, and I see no one complaining. Take the mechanistic and insatiable greed of Wall Street out of the equation, and we will make insurance a practical calculation of risk and payments again.

It's time to quit pussy footing around with these people. They are prepared to lay economic waste to the coast by removing a key underpining for all economic activity. Without insurance there are no homes, no cars on the street, no business and so no jobs. The executives of these companies are a greater threat to us than the gangbanger on the corner with a .40 caliber tucked in his wasteband. We should treat the insurance crime lords and their agents in the same way: as a dangerous criminal element that we can not get off our streets soon enough.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK wetlands news rebirth Debrisville Federal Flood 8-29 Rising Tide Remember insurance

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Ship of Fools

| "Ship of fools on a cruel sea Ship of fools sail away from me" -- Robert Hunter, "Ship of Fools" by the Grateful Dead |

Are we crazy to be here, or crazy because we're here? For everyone who is struggling with their insurer, their contractors, their family and their very sanity, should we all be taking Robert Hunter's advice and not raise out flag upon a ship of fools?

That's the advice that a commenter named Jill gives to Metroblogger Craig Giesecke on his post I've got to get a-waaaaay.... ", in which he candidly discusses his own struggles with life here and his wife's depression. In spite of his troubles Giesecke quickly responds that they have no plans to leave the support network of friend and family that offers their best hope.

As someone who is all in on the river card, I desperately wanted to jump into the fray, to say: no, don't go, that's not the answer. I did not. I was not here before the flood, not for 20 years. I didn't suffer the losses people like Craig and his wife suffered, and I am not plagued by the demons haunting the people who staid or returned quickly, and found all of their worldly possessions in ruins. Anything I might say is probably just rationalization of my own decision to come. I kept silent.

Then I read a reply post by Jack Ware Humanity, you never had it to begin with. about his own struggles and how he handles them, mostly by keeping busy on working on the home he has purchased. But he also spoke about his own relationship to people in the last year, about how difficult we have all become. I thought there was a common thread to the entire discussion that was being glossed over in the stay-or-go debate, and the discussion of the state of people in post-flood depression that don't have Chris Rose's insurance plan. I began a reply, partly to Ware and party to Giesecke (both of whom I know only through their writings), which became so long I decided to finish it here.

Ware says at one point:

In philosophy there's something called Phenomenology and Phenomenology leads to Ontology where there are all kinds of things, including identity (if you like math) and (my favorite lately) the Ship of Theseus. New Orleans is essentially a contemporary Ship of Theseus. And most of the people I know that are having a particularly hard time living here now are wrestling with this metaphysical question (identity vs. the Ship of Theseus) whether they realize it or not. Framing the question in this way made things much easier on me...

The Ship of Theseus (if you didn't follow the link) was a venerated icon of ancient Greece that was kept by constantly repaired until not a stick of the original remained. The question the Greeks philosophers could not help asking: was what remained truly the Ship of Theseus? The answer for New Orleans is yes. The city I left in 1986 was not the city of my childhood. The city I returned to last Spring was neither the city of my childhood nor that of 1986. All are recognizably New Orleans.

While the city is a product of its landscape as much as any other place, New Orleans is only partially about place in a geographical or architectural sense. What really makes it the city we love is the people of the place and how we live together (or fail to live together). Where or what we eat or drink together is not as important as that we do. The musician and the club we hear them in is not as important as the music, and that we are all there hearing it together.

The flood uprooted the shared social space that is New Orleans, the complex set of personal connections that truly make up the city of Orleanians (as opposed to the stage set by the river). Almost everyone was forced out of their home and into a new one. Those who were not saw their sliver neighborhoods transformed by a influx of new comers. The displaced who returned found most friends and neighbors somewhere other than where they have left them, some far away with no immediate prospect to return. In the midst of all of this confusion, some who stayed or returned have decided to leave. The city has undergone a displacement of people not seen in the developed world since post-WWII Europe.

All those who remain suffer not from the loss of a favorite restaurant, or the one-way flight of a favorite musician. They suffer because that social web, the very few degrees of separation and a common sense of ourselves as Orleanians, the very fabric of the place is torn and frayed by the flood. That damage to our social environment is why Ware finds solace in the solitude of working on his house.

Giesecke's reply to Jill, that he and his wife will not choose to leave for fear of losing their support network of friends and family, however disrupted it may be, says it all. I said I would stay out of their problem, but I can't resist suggesting that is a good choice. You cannot heal the profound psychic wound so many have by leaving, any more than you could save a severed finger by going to the emergency room but leaving the finger behind.

The backdrop of our lives, the homes still bearing the rescue marks with little sign of work, the continually sprouting debris piles, the businesses not returned that we all relied upon: all of these will be bearable until we can make them whole again (or as whole as our aging city ever was) if we can heal the real damage to ourselves as a community. It can all be borne if enough of us return and stay, to support each other, if enough of us willingly accept our new neighbors like the old, and recognize that they are one of us: the self-elect who have chosen to come home.

Evacuating to the community of exiles in some distant city, however clean and efficient, will not heal the loss. Expatriation would be a purgatory of longing and of guilt. I know that place of longing. I lived their for most of two decades. And I know the new torture of guilt, the profoundly empathic survivor's guilt that possessed me after August 29 of 2005. It is in large part why I am home. If you are contemplating throwing in the towel, consider this: no matter how wonderful the place you land, it will never quite be home. The places I spent the last decade were wonderful places to live and raise a family, but I connected closely to no one. There was something missing about the people and the way they lived, something that led me to speak of emigrating from New Orleans to the United States.

It might be easier for someone to leave now, to find a community of like exiles in Austin or inside the Houston beltway, people from home to whom it would be easy to connect. I don't believe such an evacuation would cure anyone of the profound depression and despair they feel. I think it would at first mask it, but in the long term compound it. Every gathering of the exiles would start happily with drinks and food, but I know the sort of people we are. Soon we would talk of the last meal in New Orleans, someone would say 'remember when' of some party at home. Everyone would look around at their new comrades, and think of the people who were not there, of those scattered or left behind. Its hard to imagine any such parting ending in anything but sadness, even if masked by desperately drunken gaiety.

I understand the temptation to give up. New Orleans was never an easy place to live. Simple things people take for granted elsewhere were always dicey or difficult here (as my wife will likely never stop reminding me). The flood has compounded that many times over. Still, if we all slowly trickle away in despair then the chance of a future homecoming, the prospect that kept me going through my years away, will diminish with every one who leaves. Our Ship of Theseus will become a collection of planks and not the artifact of our collective imaginations, of our will to be the people we believe ourselves to be. There will be no coming home.

Perhaps we are a ship of fools, but it took a certain amount of foolishness to choose to live here before the flood, a foolishness that paraded through poverty and now through rubble, that celebrates the transformation of death in the same way we celebrate all the other miletones of life, a foolishness like that of the tarot card figure the Fool that is nothing like that of the dunce cap.

I have come home, rejecting Robert Hunter's caution, and boarded the ship of fools. I did so because I think this the sanest place in America, one of the few where there is some balance between the demands of Moloch and the need to be human, both as an individual and as a part of a true community. The real ship of fools is the rest of the country, drifting into cultural civil war and an economic death spiral of greed. As I've said before, if we can't save New Orleans, then I have little hope for saving America, and I'd just assume spend the twilight years of America here, among friends.

My text for today is not Hunter's Ship of Fools, but Box of Rain. It is not a New Orleans song, but it is the one that cues up in my head whenever it all gets to0 hard or too weird, because the image of a box of rain is such a perfect New Orleans image. And it speaks to me of why I'm here, why I think we're all Here.

Walk into splintered sunlight

Inch your way through dead dreams to another land

Maybe you're tired and broken

Your tongue is twisted with words

half spoken and thoughts unclear

What do you want me to do

To do for you to see you through?

A a box of rain will ease the pain

and love will see you through.

Just a box of rain -wind and water -

Believe it if you need it,

if you don't just pass it on

Sun and shower -Wind and rain -

in and out the window

like a moth before a flame

It's just a box of rain

I don't know who put it there

Believe it if you need it

or leave it if you dare

But it's just a box of rain

or a ribbon for your hair

Such a long long time to be gone

and a short time to be there

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK wetlands news rebirth Debrisville Federal Flood 8-29 Rising Tide Remember

Saturday, November 11, 2006

The Cathedral of the Lakefront

[Updated 11-12-06]

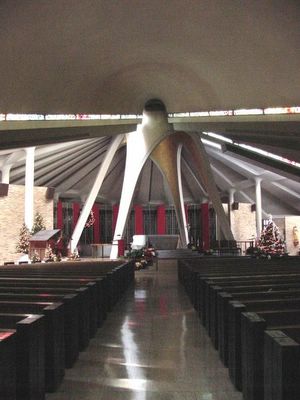

"A striking modern structure, the church . . . was called the "Cathedral of

the Lakefront" when it was dedicated by Archbishop John P. Cody [in 1963]. In

blessing the church, he told the congregation that many times he knelt in St.

Peter's in Rome during the Second Vatican Council his mind wandered across the

sea and wonder how the church would look when complete."

-- Father Paul Desroseirs

Pastor, St. Frances X. Cabrini Church

From the parish's 50th anniversary program

A landmark piece of modern architecture in a city that usually celebrates its historic roots, St. Frances Xavier Cabrini Church in the Gentilly section of New Orleans is facing imminent demolition under circumstances Tulane University architecture professor Steve Verdeber and some parishioners suggest are suspicious.

At a meeting in Cabrini's windswept parking lot on Nov. 11, just outside the red ribbons that marked a keep out zone where workers removed asbestos from the building in preparation for demolition, the architect and others questioned the manner in which the Archdiocese of New Orleans and Holy Cross School obtained the rights to demolish the property. Holy Cross plans to build a new campus at the Gentilly site to replace their flood damaged Ninth Ward home.

According to parishioners, a meeting held earlier this year to discuss the churches fate had no agenda listing potential transfer of the church, which is owned building and property by the parish, to the archdiocese for demolition. Several people who attended the parish meeting left before the issue was raised and a vote was taken, unaware that the question was even scheduled. They said the meeting did not represent the wishes of the majority of parishioners.

Verdeber and active parishioner David Villarrubia spent part of last week at City Hall researching how a demolition permit was issued in the name of the demolition company. There was no indication on the paperwork who was the client that requested demolition. The permit fee was paid by the demolition company. Verdeber and Villarrubia are working with an attorney to try to stay the questionable demolition, starting from the fact that it is not clear that either the archdiocese or Holy Cross School has any legal authority to demolish the parish's property.

Both indicated there was no desire to prevent Holy Cross School from coming. Only to have a dialogue about the future of the architecturally significant church building on the two-city-block square property. In an earlier Times-Picayune article, a spokesman for Holy Cross suggested it was too large to be of any use to the school, but parishioners on Saturday pointed out that Holy Cross routinely used it for ring masses and other ceremonies, and that virtually all of the Catholic high schools in the city used either Cabrini or St. Dominic for such events because they were the only churches large enough to accommodate them.

Some parishioners complained of the treatment of the valuable contents of the church. The altar, a large single-piece of marble imported from Italy, was dropped during its removal from the church and broken. Mosaics that decorated the church were seen broken and in pieces, and the church vestments were found tossed into a trash pile where they were rescued by a parishioner.

Villarrubia said they were unable to determine the disposition of other removed contents of the church, including the striking wooden carving of Jesus that graced the alter. The archdiocese had promised all of those contents would be returned to the parish, which to me would indicate they recognize the archdiocese tenuous claims on the property.

The church was apparently the only one in the archdiocese to carry flood insurance, and it was suggested that the money might be diverted by the archdiocese if the church was demolished. Verdeber and Villarrubia suggested that the insurance proceeds were sufficient to pay for a full restoration of the church.

The meeting broke up after one parishioner read from St. Francis Xavier Cabrini's life story from a book of saints while another distributed cards bearing a likeness of the saint on one side and a prayer to her on the other. Another parishioner led the group in the prayer for intercession from the card, with an elderly resident in loudly offering "save our church" when the prayer reached the "intercede for us that the favor we now ask may be granted".

[Below is the original post of Nov. 11, 2006:]

I have written before about Cabrini Church, a signature example of modern architecture in New Orleans by the same architects and engineers that built the Rivergate. Among those architects was my father, who was project architect for both buildings.

My attachment is certainly in part sentimental. The building is not a classic piece of New Orleans architecture and is less than fifty years old. Still, I wonder what perservationists fifty or one hundred years from now will think of us for demolishing such architectural landmarks of the 20th Century as this church and the Rivergate. The building was given an award by the Church Architectural Guild of America in 1962. Even the school plant, also by Curtis and Davis Architects, was given an Award of Merit by the American Institute of Architects in 1952. The same architect and engineer who crafted the flowing roof of the Rivergate designed and built the striking roof and interior buttresses of Cabrini. While not yet historic, it is clearly architecturally significant.

The church was inundated like all of Gentilly in the Federal Flood, then left unremediated by the Archdiocese of New Orleans in what can only be an act of deliberate demolition by neglect. Earlier this year, the badly flooded Holy Cross High School in the Ninth Ward announced it would locate out of that neighborhood, and narrowed its choices for a new site to that of Cabrini church and school, and a parcel of land in suburban Kenner, La.

I think everyone committed to New Orleans was pleased to learn that they elected to remain in the city, choosing the Cabrini site on Paris Avenue near the lakefront. However, as part of the arrangement, the entire campus is to be demolished to make way for a "new, state-of-the-art school," according to Bill Chauvin, chairman of Holy Cross' governing board.

Three members of the Historic District Landmark Commission voted this week for a study of the value of the church as historic landmark, a largely symbolic move as a permit for demolition has already been issued. People who have visited the site report that crews are now removing asbestos, and that once their works is completed demolition will begin, sometime the week of Nov. 13th.

"We had two choices,"Chauvin said, referring to a site offered Holy Cross in Kenner. "Had we known of this concern, it may have impacted the board's decision." Chauvin said the Holy Cross governing board looked at the feasibility of retaining the church "but it just didn't work."

An architect at Tulane University disagrees, Steven Verdeber, and is looking into stopping the demolition. He suggests that a building of this size could easily be incorporated into a site the size of Cabrini, which covers four city blocks.

Chauvin suggests its inappropriate to raise this issue at this time, after what he termed "an open and transparent process." But an earlier report I had (I am searching right now for the original email if it was in fact an email and not a blog comment) suggests that the decision to abandon the church was the opposite. In the early days after Katrina, a poorly noticed and attended meeting of a handful of parishioners met at St. Pius the X Church in nearby Lake Vista and agreed to the Archdiocese decision to abandon the site.

Verdeber is searching for an attorney to block the demolition, but I don't know that he has enough time. Cabrini will join the scores of landmark buildings great and small being demolished helter-skelter in the post-Flood city.

parishioners and friends of Cabrini will gather on Saturday at the church at 1 pm this Saturday, Nov. 11, to celebrate the feast day of St. Frances X. Cabrini and to say goodbye to the church. (The actual feast day is Monday, Nov. 13). A few days later, another signature building from New Orleans' pre-flood profile will be gone.

Some photos of the church in its pre-Flood glory can be found here on Flickr.com under the tag Gentilly and Cabrini. My original post on the church, In The Brown Zone with Mother Cabrini, can be found here, and a reading of the post for the WTUL-FM program Community Gumbo can be found here.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK wetlands news rebirth Debrisville Federal Flood 8-29 Rising Tide Remember Gentilly Cabrini Church St. Frances Xavier Cabrini

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Signs of life in City Park

Turtles basking on a log in the lagoons off City Park Avenue

The turtles basking in the sun on a log in the lagoons along City Park Avenue in New Orleans' City Park are a subtle sign of the park's slow recovery. These lagoons were innundated with lake water by the flood (as was the rest of the city), and filled with downed trees and debris.

The lagoons are linked to Bayou St. John and through that waterway to the lake, so some salinity from the lake's brackish water is natural, but I wondered at how the likely higher salinity along with the contamination of the city's floodwater would affect these lagoons and the birds, fish and turtles I have associated with them since childhood. A pre-flood Save Our Lake report on the water quality of Bayou St. John and the lagoons found historically low salinity the years right before the Federal Flood. I can't find a study of the aftermath of the flood

These turtles are a small but important sign that the lagoons are likely going to make it. On this day's lunchtime walk the fish were snapping at the surface for their own midday meal, and a diving duck breasted the water like a small Loch Ness monster. If the lagoons had died, or if the stand of centuries-old live oaks that surround them had all been lost, a part of the city's heart would have died with it.

The park has been a central part of my entire life in New Orleans. While I looked uptown for affordable, dry houses that would more closely meet my wife and daughter's picture of what a proper New Orleans house looks like, I am glad we landed in our craftsman double shotgun on a high peninsula off of the Metairie ridge. It puts me back in proximity to the park of my youth, and allows me to see it in a new light.

All through my childhood in a house on Egret Street just off Robert E. Lee the area where I live now along City Park Avenue was the far end of the park to me. If I ventured this far on my bycicle, reaching the City Park Avenue lagoons was to reach the limit, and beyond oak canopy I peered into a city vastly different than the 20th century surbaban enclaves I knew to the north, as if cycling the winding park roads allowed me to travel back in time to an older and different city, one I usually only glimpsed from out my parents' car window.

Now I enter the park from the south, crossing City Park Avenue, and like anything approached from a new perspective I see it in new ways. The bridges that once marked for me the park's southern limit are my entry. I prefer to walk almost up to the Casino to cross the steeply curved, Japanese style bridge there. The sterile childhood vista of the north gold course is replaced by the stands of live oaks that define the park's southern end. The rump remains of ancient Bayou Metairie that form the lagoons of the south end are more natural than those that line the golf courses to the north. Vegetation lines the banks, and fallen logs shelter fish and sun turtles. Carefully shaped over a century into its current citified parkscape, it still hints at what the place might have looked like when first glimpsed by Bienville.

The north end of the park offered its own, wilder version of citified nature when I was very small. Before the construction of the north golf course it was a wild space where snakes could be caught and packs of feral dogs ran. I viewed it with the same respectful fear as a medieval villager looking on a dark wood, and would only venture into the heart of the north end when the alphas of my own nearly feral pack of boys carried me there, an unwilling tagger on. After the construction of the north course, a tree house was built by children older than us in one of the park's trees, and adopted by us as a retreat where we could talk away hot afternoons high up in the breeze under the shade of the canopy.

The long lagoon along Marconi Drive once hosted water skiers, including a jump ramp, before the construction of the shell causeway for Filmore Avenue bisected the long run. My father would sometimes park under the trees along Marconi so we could sit and watch them make the long run up to the ramp and launch themselves into the air. In this same stretch, I once saw an Amphicar launched and watched it take a spin around the lagoon.

From fifth through eight grade, I attended Christian Brothers School in the old McFadden Mansion in the park. Nestled into the older golf courses of the south end of the park, it was set in its own small parkland with its own lagoon. There were several stone constructions, one clearly meant as a grotto (and I wonder today why there was no statue of the Virgin or some saint there), and a raised overlook lined by a brick wall that in fifth grade we thought of as The Fort.

On one of my children's first visits to New Orleans, I made a point of taking them to then newly refurbished Story Land, a small children's park of climable children's sculptures of figures from childhood stories, a wonderland of figures from Mother Goose, Pinnochio's whale, a small pirate ship, and many giant toadstools. We road the flying horses and and the minature train that circles the park's south end. We walked the south end lagoons, and fed the geese and ducks that live there in part on the kindness of strangers with day-old french bread.

On my recent walks I often wondered which attractions might never return. Unlike Audubon Park which is subsidized by a property tax, City Park depends almost entirely on the revenue of its ruined attractions to find itself. The driving range and tennis courts are back, but the golf courses remain a wild tangle. The government seems reluctant to spend money on something as trivial as one of the nation's largest and most active urban parks. It has not been clear that the park was going to recover.

Then, on my return trip (this time with camera) to look for the basking turtles, I found a railway repair company working on the miniature train tracks and confirmed with one of the crew that the tracks were being repaired and not (as I feared) removed. If the life of the lagoons is making a post-flood comeback and the trains are coming back, can the rental boats be far behind? It looks as if this one corner of New Orleans, like so many others, is pulling itself by its bootstraps and getting back together.

Signs of a crew working on the miniature railway tracks along City Park Avenue in City Park.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK City Park Mid-City

Friday, November 03, 2006

White Devils 1, Mau-Maus 0

-- Jake Blues in The Blues Brothers

If you find the headline on this post offensive, it's not half as repugnant as the ugly, race-blinded arguments made at yesterday's New Orleans City Council meeting over the creation of an Office of Inspector General for city government. I think the world view the title suggest is more ridiculous than offensive, just like the suggestion by a few vocal opponents that the establishment of a watchdog office over city government is a plot by white people to attack black politicians.

The Times-Picayune reported " . . . activists including Albert "Chui" Clark and Dyan French Cole attacked the proposal as an effort by white politicians to target black officials. They also used the occasion to denounce the condition of the city's public schools and to praise Criminal District Judge Charles Elloie, who was suspended from his job recently by the Louisiana Supreme Court pending the outcome of an investigation into alleged judicial misconduct." What, was time up before they could get around to defending Dollar Bill?

My only hope is that anyone who stands up for the status quo of the openly corrupt and incompetent Orleans Parish School Board or defends Judge Elloie on purely racial identify grounds will find no real support in any community in the city, black or white. Sadly, that's not entirely true. Even The Cynthias (veteran city council members Cynthia Hedge-Morrell and Cynthia Willard-Lewis who have obstructed the proposal all year) say silently through the entire debate, giving tacit approval to the race bating from the audience podium.

The idea for such an Inspector General to oversee city government was overwhelmingly approved by a nearly seven-to-three margin in a 1995 city wide election, a result that would require substantial support among the city's predominantly black voters. One speaker asked "Why didn't white folks do this when they had power"? Well, because the last white mayor was in the 1970s, and the issue has only come to fruition in the last decade. You want to exhume the corpse of Robert Maestri and indict it or parade it through the streets, that's fine. I'm worried about who's in power now.

I struggled for a while to find the rational thread inside their reported arguments, and failed. There is no logic, simply a visceral appeal to racial identify, fueled I suspect by anger at the difficulty many black Orleanians face trying to come home. The city today is predominately white, and it is going to stay that way unless we all figure out how to put all this behind us, how to relegate the reflexive mau-mauism exhibited Thursday to the past, to same sort of embarrassing tableau in the Historical Wax Museum of Louisiana Stupidity where we find David Duke.

Put simply: we don't have time for this shit.

The purpose of resurrecting the long dormant Inspector General proposal is to satisfy the federal bean counters who hold the purse strings of recovery money. These bean counters are under the close supervision of a government controlled by a party that has a well established pattern and practice of attempting to illegally disenfranchise black voters, a party I believe revels in the storm-sent racial cleansing of the city.

By trying to block this initiative, these self-annointed activists are playing right into their hands.

I want everyone to come home who is returning to rebuild the city as a better place. I have no use for people who would tear it down or those would would settle for the status quo antedeluvian. People who would defend the old OPSB or Judge Elloise, frankly they are an obstacle; no, a real direct threat to the recovery of the city. If they aren't home, I would just assume they stay wherever the hell they are. Let me know where that is so we can send Jimmy Reiss and the rest of the Knights of the Invisible Hand there with them.

I want this city rebuilt so that those of us who chose to live in a diverse community together can get on with the serious business of a true Reconstruction, one in which Dr. Martin Luther King's children of former slaves and the children of former slave owners can live together in a better place than we had before, without the reflexive racism on both sides that has colored our past.

If the rebirth of the city fails, if New Orleans becomes a tourist museum tableaux of the City That Care Forgot set amid the condos of the white and wealthy who come every year for The Mardi Gras, I believe historians will look back at this moment and remember The Cynthias and their henchmen in the audience, will remember this as the moment all the old demons reached up out of the ground and dragged our last hopes down to hell.

Katrina NOLA New Orleans Hurricane Katrina Think New Orleans Louisiana FEMA levees flooding Corps of Engineers We Are Not OK wetlands news rebirth Debrisville Federal Flood 8-29 Rising Tide Remember

"And when we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard nor welcome, but when we are silent we are still afraid. So it is better to speak remembering we were never meant to survive." -- Audie Lorde

Any copyrighted material presented here is done so for the purposes of news reporting and comment consistent with USC 17 Chapter 1 Title 107.